Gartner told us that by 2022, 80% of us would have moved to a more product-centric IT operating model. What does this mean, and more specifically, what does it mean for us as software engineering consultants?

Products - Delivering Value

First, some definitions. What do we mean by “Product”? For me, this is a very business-oriented term. Say you’re a dairy farm, your products might be milk, cheese, ice-cream. This maps to the Agile definition of “Product” as a vehicle to deliver value; as in “Product Owner” - perhaps the cheesemaker in the dairy - the person who understands how applications impact their business and is ultimately responsible for deciding which software changes are built and released by a team. And the important concepts behind product-oriented teams, for us software engineers, are twofold.

One, there is the concept of funding. For a business to fund a product rather than a project implies no end date to the funding stream, which fits in much better with agile practices, for example we only plan in detail for the next sprint, and it supports the creation of long-lived teams which can become much more efficient at delivery.

Second, there is the concept of having full focus on delivering business value. This isn’t new, and is probably the goal for all sprint teams, but anyone who’s worked in an agile team will have hit that sprint where they have to deliver tech debt - perhaps they have to patch some libraries, or restructure their data schemas to improve application performance, or do something in the DevOps space such as implement blue/green releases. The product owner is on board with the need to do these things, but isn’t really that interested in the implementation and really just wants these problems to “go away” so they can get back to more important sprint stories. Hence the emphasis on product teams focusing on value delivery and customer satisfaction.

Unicorns

You’ve probably spotted the flaw in this idea - how can the IT teams focus solely on “value delivery” and STILL provide something performant and secure? How does all the other stuff get done? What about creating delivery pipelines and test frameworks and patching strategies and scaling mechanisms? What about all the DevOps tasks such as making our app supportable and observable? This HAS to be done, but it isn’t accounted for in the job definition of product-centric teams.

Zones of Repeatability

The good news about all the important DevOps style work which our product-centric teams don’t have time to do is that whilst it’s heavyweight work, most of it is highly repeatable. This means that solutions can be shared between product teams.

Platforms - the new Platforms!

In other words, what we need is a “common platform”. This isn’t a new idea, and exists in some form or other in most companies - complete with a Platform Team in charge of creating and maintaining it. These platforms, however, are often destined for failure - and by failure, I mean they do not get used and do not provide the advantages that they promised, for a number of common reasons that we would want to avoid when defining our platform for supporting product-centric teams. I’ll list out some of the major pitfalls here

1. The Gap

You might be familiar with the idea of “Goldilocks problems” - in the story of Goldilocks and the three bears, she always tries the two extremes before she gets it right. The first porridge is far too hot, the second is far too cold. Similar things tend to happen to platform teams when they are given the remit to create a common developer platform - on the one hand, they create a platform which doesn’t do enough for the developer and as such, isn’t an accelerator and doesn’t save them any time. An example of this might be when a company first decides to build a shared platform and hires some platform engineers with a very loose remit. The engineers think of some tools the devs might like, and provision them somewhere, and create some roles and access rights, but without an understanding of what the developers do (or want to do) this isn’t going to be usable.

2. Should vs Could

Fellow blogger Chris Burns came up with this title. The concept comes from the speech by Dr. Ian Malcolm in Jurassic Park - “your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, that they didn’t stop to think if they should”. This might be what happens when you throw money and resources at a platform problem - you hire the best DevOps engineers, they have incredible skills with tools like Jenkins - they can script their way around a whole bunch of issues and failures, but again, they’re not focussed on the right problem. Their remit is still too loose and they haven’t got an eye on who their customer is, and because customer satisfaction isn’t set as top of their priorities, they’ll create a monster that is frankly unusable by the dev team and quite possibly also a security hazard. We’ve seen examples of this where the developer requests a job to tear down an environment, for example. Perhaps they have a bad test which relies on certain data in the database - the solution to this is to rewrite the test. The platform team’s solution might be to create some heinous post-cleanup script to reintroduce the required data before the test runs. Yes you can do that - but it’s not the right answer!

3. Devs in Chains

This pitfall is at the reverse end of the “Goldilocks Problem” - rather than having a platform that is too loosely defined, you create one that is too locked down. It might be very efficient at what it does, but if it doesn’t do what the developers need it’s still a failure because they won’t use it. For example, perhaps you provide build pipelines without the ability to edit what they do. They may deploy containers very efficiently; but what if you suddenly want to add a serverless function to your architecture? What if you want to run a different set of tests? The platform should not dictate what the dev teams can do to this level. Such restrictive platforms could also result in security issues. Developers are an extremely creative bunch, if you try to lock down access to the databases, for example, some bright spark might realise that if they simply add an ‘apt get install postgres’ into the Dockerfile of the Java applications deployed into their Kubernetes cluster, they could then ssh into the pod when it was deployed and use the PostgreSQL client installed into the container as a “back door” to access the database. Argh!

A New Mindset

So what’s the solution? We as developers know it very well. When we’re building applications for our product owners, we work in an agile way - we create friendly “user stories” and break them down into tasks that can be delivered quickly, we build a minimum viable product and get it out for some user feedback and then we iteratively improve from there. So why on earth don’t we do that when we build platforms?! Why do we hire a bunch of highly talented platform engineers and hide them away behind a service desk interface, creating the “Dev/Ops gap” we have been trying so hard to break down all these years? All that we need is for the platform team to reverse its mindset. To remember that the developer is the customer in this scenario, and in the same way as IT customers the whole world over, they do not really know what they want.

Needs versus Requirements

If a platform engineer adopts this customer-facing mindset and sits down with a developer to list out what they want, the developer might say “I want access to the production servers and all the databases”. Our engineer needs to be ready here to translate this into what they actually need, which is the ability to deploy applications, to observe application behaviour, and to make changes when necessary. This isn’t quite how the dev has phrased it! So we need to bring to the table all the skills from agile methodologies and also from practices such as domain-driven design to make sure we are getting our customer requirements right.

Build an MVP

When you look at the CNCF Cloud Native landscape it’s easy to become overwhelmed as to how you are going to build a platform which covers off all of these boxes. Of course, the way to break down this complexity is to start with a Minimum Viable Platform the same way we would build an MVP for a complex application. Figure out what you need first, figure out where the risk is, get those bits in place and working and iteratively improve from there.

The Paved Road

The secret to not being too restrictive is to follow Netflix’s example of building a “paved road” across the CNCF landscape without locking dev teams down to a certain path. For example, we know we will need some kind of pipeline automation software to run builds and other deployment-related jobs. But which one to use? It doesn’t really matter - just make sure that your platform is built in a sufficiently layered, pluggable way and then put in a suggested tool - say, Tekton chains - and if there is one team who REALLY want to use Concourse for some reason, they are welcome to configure the platform and change the pipeline tool. The “paved road” is there as an accelerator for teams who don’t have an opinion on which pipeline to use, but they are not forced to use this route.

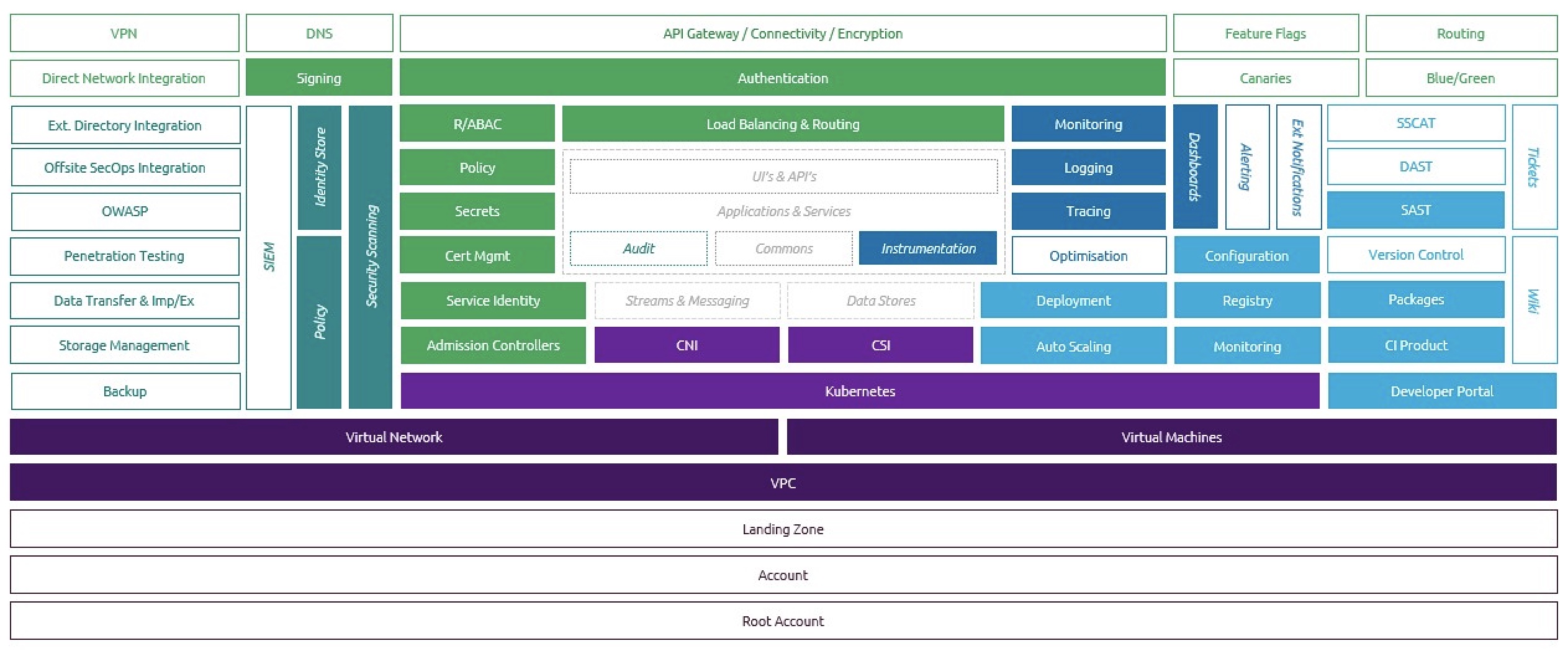

Our Opinionated Stack

The Cloud Development team at Capgemini have created our own “Paved Road” through the CNCF landscape. We’ve called it CREATE - the Cloud Ready Environment for Application Test and Execution. It takes the principles of zero trust; customer centricity; automation first; separation of concerns. It will be open-sourced and uses mainly open source components. We’ve assumed that the cloud platform will be Kubernetes-as-a-service, as this is a good abstraction from specific cloud vendors whilst allowing scale-to-zero for maximum compute efficiency. We have defined the necessary pods for both tooling and deployment using Terraform and Helm. We’ve separated out Continuous Integration from Continuous Delivery, with separate pipelines and separate permissions for each workflow, and we add Harbor as a place where built artifacts can be interrogated, signed and stored securely.

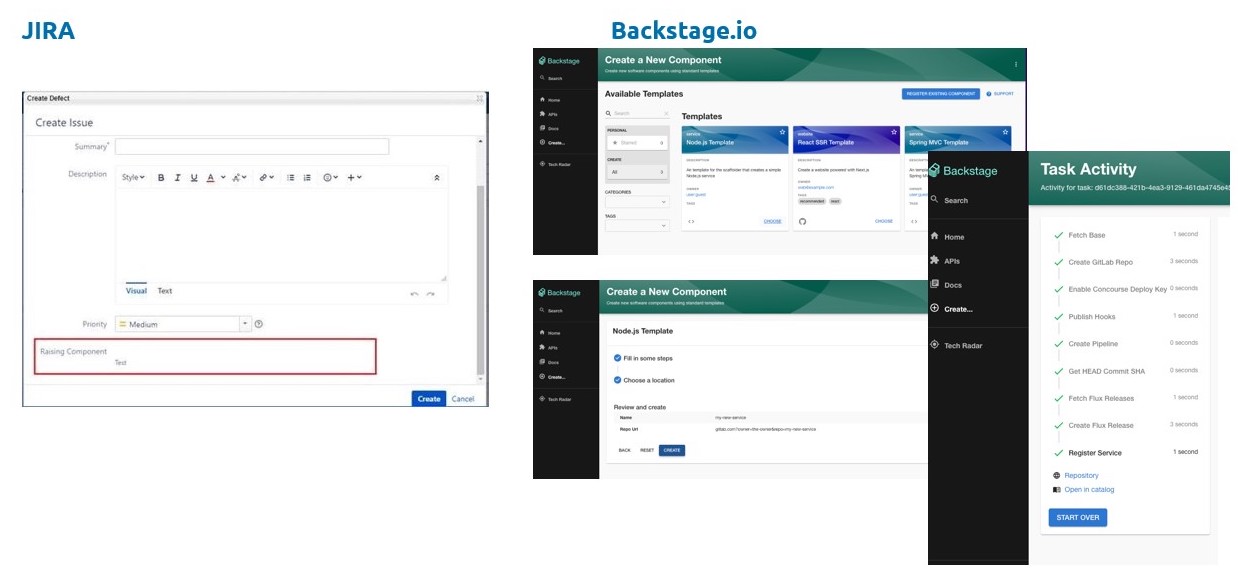

We’ve used the wonderful Backstage portal from Spotify to build our developer interface - it’s so much more friendly and intuitive than trying a “square peg/ round hole” approach of building a portal out of service desk or issue tracking software.

The remit of CREATE is to provide a catalogue of template applications - a React app, for example, and a Spring Boot app - from which the developer can choose what best fits their need. It will then manage the whole GitOps workflow - creating in the cloud the infrastructure for running the build (pipelines, quality analysis tools etc) and also the infrastructure for hosting the application. It provides a template to deploy useful peripherals such as a credentials vault, authentication, monitoring/logging/tracing tools. We don’t mind which ones - we provide a default, but they’re pluggable; we’re more attached to the principles than the tooling choice itself. CREATE will then set up a repository for the template application, build and deploy it, and leave the build pipeline waiting for changes. It will automatically auto-scale based on load. And all this in under an hour. Yes it has its limitations - it’s designed for containerised applications hosted on Kubernetes - but anyone who’s worked on applications in this space will appreciate just how much time and effort it will save.

If you’d like to find out more about CREATE, and receive notification of when we release our MVP, please get in touch with myself or Chris Burns via Linkedin.