Who can resist the opportunity to join a Hackathon? Certainly not the engineers in Capgemini’s Applied Innovation Exchange (AIE); fast-turnaround cutting-edge product development is what we do. So when Capgemini Financial Services announced a global virtual IBM Hyperledger Hackathon, a team was thrown together.

The AIE is split across the UK, and for this project we had team members from the Aston AIE and the “virtual” AIE, those of us unlucky enough not to live in Birmingham or London! The virtual AIE had been focussing on Smart Contracts and Blockchain using Hyperledger for a while, so we had some of the relevant skills and a bit of background already.

We could choose from a number of use cases, or we could choose our own if backed by a client sponsor. Finding a use case for blockchain is possibly one of the hardest aspects of a blockchain project, so we went with one of our existing client ideas - which closely tied with the hackathon requirements anyway - and set out to build a smart contract system for the car lease industry.

As documented in a previous article, it helps to follow some basic criteria around whether a use case is suitable for blockchain:

- Does it have a database with shared write access?

- Is there an element of trust?

- Is functional consensus required?

For a car lease company, it’s possible to meet these criteria. There are several parties who may wish to input data into the car lease database - the client (policyholder) themselves, the insurance company, garages who carry out repair, sources to verify the value of a replacement car, possibly the police or other witnesses to accidents, third party claimants if an incident involves many people. These parties have different motives so there is a trust aspect, and consensus has to be reached on the outcome of a claim.

Good to go! We had a rough plan to produce a front-end for use by the policyholder and a Hyperledger smart contract with inputs from the various parties. We split the work so that the team who were sat together in Aston could focus on the front end and Node JS APIs, and the remote team could focus on Hyperledger.

Use Cases

For our minimum viable product we chose the use case whereby a policy holder has had an accident involving no other vehicles, and has caused damage to the car of sufficient magnitude that it’s cheaper to write off the car than to fix it, and so the claimant will receive a payout. This involves just a few actors and data sources - the claimant themselves, the garage who report on the value of the damage, a car valuation service and possibly IoT data sent directly from sensors on the car.

For a stretch case we wanted push notifications to allow the claimant to be notified of changes to their claim status without having to log on to the application.

For a further stretch case we considered two drivers involved in a crash, so a second claimant is thrown into the mix.

For the purposes of the hackathon, the plan was to mock up the third party data sources as RESTful APIs with mock data, and run specific use cases through the blockchain code.

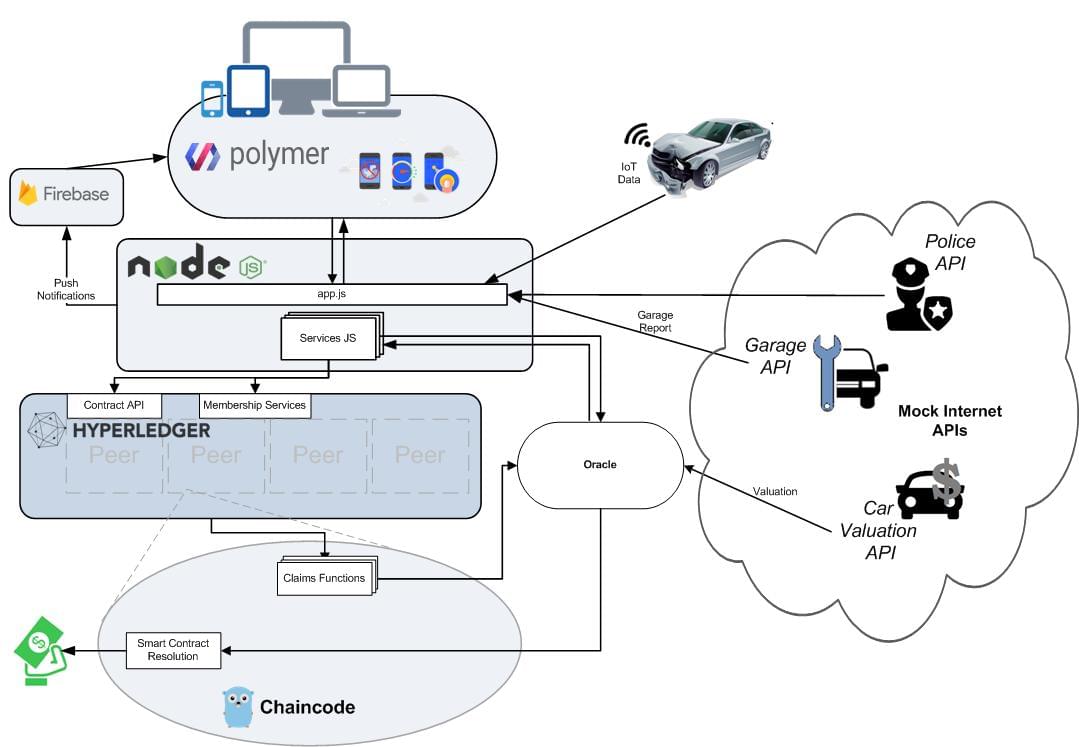

High Level Architecture

The front end would be written using Polymer, providing responsive views for mobile or desktop apps. Polymer was chosen as a result of its strong standards compliance, which allowed us to onboard new joiners with only very basic web experience very quickly, and its true encapsulation of components, which allowed us to more easily and efficiently divide our backlog into components without worrying about how others are implementing their code. In addition, the Polymer starter-kit provides a great place to start, instantly giving us a responsive, progressive web-app, with offline support out of the box. The central application would be written on a NodeJS platform, calling the Hyperledger RESTful APIs to pass data to the blockchain. NodeJS was chosen partly because the technology fits the chatty, multi-HTTP message architecture of calling multiple RESTful APIs across multiple devices, partly because we could make use of the Hyperledger Fabric API available for NodeJS, also because it allowed us to pair server-side JavaScript with a JavaScript client, in turn facilitating us manipulating JSON easily and in the same way on both sides of a request, and partly because we already had a starter-for-ten written in NodeJS from the IBM Bluemix car lease demo application and in a hackathon, you need every helping hand you can get…

The push notifications were built using Firebase and the PolymerFire series of Firebase enabled WebComponents. Using Firebase gave us an instant WebPush compatible server and the PolymerFire elements allowed us to simply drop 2 HTML elements and one small JS file (for instantiating Firebase messaging) into our page and start receiving notifications instantly without having to install an app.

Blockchain claims functions would be written in Go, this was so that we could take advantage of the Hyperledger Go API.

Oracles

In our system, the chaincode needs to obtain a car valuation in order to establish if a vehicle should be written-off. In theory, the chaincode could make an http request to a third party car valuation service directly, but in practice this would not work. This is because every peer within a Hyperledger Fabric system executes the same chaincode independently. Therefore, every action within the chaincode must be deterministic in nature, otherwise there could be a disagreement on the current state of the system. If, for example, each peer made a direct REST call to a valuation service, there is no way to guarantee that the response to each would be the same, which could result in some peers considering a vehicle to be a write-off, whilst others do not.

To overcome this, we utilized the Oracle pattern. An oracle is by definition “an agency of divine communication” and in the blockchain world the concept is generally used to describe an entity that fetches data on your behalf that you cannot, or don’t want to fetch yourself.

Our oracle service is implemented as an asynchronous REST endpoint in the Node JS server and works as follows:

- Each Fabric peer reaches a state in which a car valuation is required, and sends a REST request to the oracle service. This request contains all the required car information from our mock APIs and transferring that information into , along with the id of the blockchain transaction which triggered the invocation.

- The service returns immediately with a 202 ACCEPTED response.

- A car valuation is then obtained (via the third-party Edmunds api) on behalf of the chaincode

- The oracle then triggers an invocation into the Fabric blockchain with the car valuation details. Only one invocation is made, even though the endpoint may have been called my multiple peers independently.

- The chaincode will only accept a car valuation from a specific oracle member, and if the origin certificate matches up correctly it will now have access to a car valuation and can make decisions regarding the write-off status of a vehicle based on this.

Ideally, in a production ready system, the oracle would collate a number of valuations from different sources and establish a median price, rather than trusting the valuation from a single source. We felt that this was not required for a proof-of-concept hackathon implementation.

Deployment Architecture

We used Docker containers to emulate four Hyperledger Fabric peers and a membership service; this allowed the development and IBM Bluemix cloud environments to be the same. For development, we used Vagrant to configure a VirtualBox and ran the Docker images there; on Bluemix you can upload your Docker image to the cloud. Both the Node and Polymer applications run in CloudFoundry runtimes on IBM Bluemix PaaS. As neither framework has specific ties into their runtime, we felt it unnecessary to use separate containers for these two simple apps.

Project Management

The team worked in an agile way, using Trello to capture agile user stories and break them down into assignable tasks. We had a remote daily standup and linked sprint demos into the AIE weekly demo sessions to give us something to aim for. We encourage traceability as being key in ensuring that our teams succeed when their size fluctuates, and as such we have 2-way traceability between our user stories/tasks and our Pull Requests on GitHub. These four essential components helped the project stay on track despite remote and fluctuating team members, it was a real success story to see.

Modelling

First step was to take our user stories and create a JSON data model which could be used by each layer of the architecture. Starting out with a policy holder and a vehicle, we broke out the concepts of a policy and a claim, deciding the important attributes of each object.

Chaincode

Once we had our model and workflow, we could separate out the chaincode functions we would need. Hyperledger Go “objects” have three public method which are called by Hyperledger Fabric - Init() which is called once when a peer is started and sets up initial state, Invoke() which as the name implies can invoke changes to the blockchain - parameters to this method can define which blockchain changes are made, and Query() which is used to examine the current state of the blockchain.

Business Logic

The Node JS application was where the business logic of the system really resided. Here went the logic of which oracles should be called when, and Event Listeners were configured to listen for blockchain events

APIs

We used a pre-built Node + ExpressJS generator to initialize our server-side app, and started to expand it out by adding in the Hyperledger Fabric SDK. In order to document the APIs that we serve, we use a Swagger JSDoc node module in combination with a separate pre-existing Swagger UI instance. This allows us to have a single application that is able to request documentation for all of our running APIs, allowing us to more easily keep track of our API microservices.

Authorisation and Authentication

The Hyperledger member service was used to define users; the Node JS application called the Hyperledger Fabric REST APIs with user information to authenticate and generate a token. This token could be used for a session to make Hyperledger Fabric API calls and define who was calling the chaincode. Within the chain code, authorisation compared whether the calling user was allowed to trigger each set of functionality.

Outcomes, Lessons Learned

We’ve all learned a lot on this project, and we have created some valuable reusable components. The Hyperledger / Bluemix platform is impressive, as is the ability to reproduce the environment with Vagrant and Docker for local development anywhere. We’ve found some (more) cool JavaScript stacks and frameworks, and perfected our remote team working skills. So how did we do? The judges are apparently impressed with our entry, with the team being advised to apply for visas ready for the trip to the finals in India. Good luck everyone!