Once I was a serious developer, but this year all I have been allowed to do is play with Platform as a Service (PaaS) offerings. Instead of sulking, I have embraced the concept, and I think it’s time a lot of other techies did too.

Today I have been taking a frankly delicious free lunch at the Radisson Blu in Manchester courtesy of “Mendix On Tour” – not a free lunch of course but a chance for the guys at Mendix to showcase some of their success stories to potential customers. Frankly, they’re preaching to the converted – I’ve long been a Mendix fan. Any company that rewrites their entire platform in Scala to improve performance classifies as a proper tech company to me!

In very brief terms, Mendix offer a Platform as a Service to develop web front ends, business process logic plus the ability to persist to a data source. They provide a drag-and-drop development environment to allow incredibly fast development of fairly complex business applications with interfaces that will adapt to work on a variety of devices. There were numerous clients at the event, showcasing their success stories - typically a one-man development team creating a proof of concept application which was then launched by the business.

I could do that

There is a cry associated with these NoCode/LowCode PaaS offerings which will send a chill to the bones of any seasoned developer. “This is so easy, even a [insert-non-technical-role-here] can do it!” Oh help us all. All those decades and decades of refining the project deployment process, all those hours spent discovering that test-driven development really works, all those carefully crafted automated unit test suites and continuous integration builds with branching and merging and colourful alerts and dunce-hat-allocation, all those DevOps architectures with built-in monitoring points and self-documenting code and self-generating API documentation, all for nothing! Because now Lee from Marketing is going to be in charge of building the new business applications and they haven’t heard of any of these things. How long will it take them to learn? Surely at least as long as it took us computer scientists.

I exaggerate, but even at the Mendix Tour it became apparent that these issues are rearing their heads. The initial prototypes go swimmingly, but then you are left with a complex piece of business logic dangerously exposed and open to change from many fronts (i.e. any user). Mendix appeared particularly vulnerable in that the platform really expects a small development team, or even a single developer, to be working closely on the project for a short period of time. I heard many comments along the lines of, “I wish I could lock that down so people stop tampering with it”, “Nobody can touch that module, it’s mine only”, and so on.

Mendix has had version control based on Subversion since version 3, so all the necessary functionality is there – it seemed to me to be a question of process and an understanding of how to use versioning in a shared environment that was missing from the picture. There did seem to be an issue that versioning is only implemented within an application, so dependencies between applications could not be modelled – the kind of hurdles we crossed long ago in the Code world. Look at how far we’ve come with Java – from JARs to WARs to EARs to full-on containerisation. LowCode and NoCode products are only just starting up that slope.

Solidifying the Cloud

To share another story – Salesforce offerings can often be considered low-code / no-code, even though you can Java away with Salesforce to your heart’s content. On one of my recent projects, the Salesforce team got into trouble for the very high number of defects appearing in testing that one would expect to have been picked up in Unit Testing. Turns out this was because “Lee from Marketing” was running the Salesforce team with a bunch of junior developers and he’d overlooked introducing the concept of the Unit Test to them because he’d never come across it. This is reinforcing my viewpoint that us techies need to embrace the LowCode /NoCode world before the, er, lunatics start running the asylum….

There were a couple of consultancies at the Mendix Tour offering their services to help companies built their Mendix apps – I wondered if any of these had managed to define a process for larger-scale Mendix development, but from what I could glean in a quick conversation they mainly offered headcount with development experience rather than any further layers of process.

I’ve been looking at other PaaS offerings lately too, namely Websphere Cast Iron, a data orchestration platform which in its “Live” form is hosted by IBM in the cloud. It sits jarringly on many an architect’s pattern to expose all your APIs externally just so that the cloud product can align them, but for the most part and if you already have cloud components, it works well. The “development” process takes a matter of minutes, and deployment is neatly wrapped in a web API. The project were so impressed with the quick turnaround of functionality we could offer that they ended up moving some functions out of their AWS development programme and into Cast Iron. Anything where a number of API calls were being made and the result sets amalgamated could be configured and deployed by our team in a matter of minutes, compared to a good couple of days for the Java equivalent running on AWS. It does seem to me that in the future, programming may well be seen as a luxury in many projects. It’s something we all want to do, we’d all rather build our own - even if we do base everything on existing open-source libraries and just copy and paste most of our code from Stack Exchange - but is it necessarily cheaper or better? With today’s wider range of mature PaaS options and ever-decreasing service costs, perhaps not.

Cast Iron Live has expended some effort in the area of software reuse and modular components. There is the concept of a reusable “TIP”, so if you develop a message flow (or an “orchestration”, as it’s known) that you are particularly proud of, you can package it up for reuse by your peers. Yet, Cast Iron isn’t too hot on versioning – there are two different concepts of automatic versioning within the tool and neither do quite what you need or expect. Occasionally we’d be prevented from overwriting each others’ work, occasionally we wouldn’t - we never quite figured out the logic. We struggled to manage parallel changes to our orchestrations and ended up creating our own, third method of versioning involving orchestration naming conventions and a Subversion backup, and ignoring the Cast Iron offerings altogether.

It seems to me that many Low Code and No Code offerings are reaching a level of maturity where it’s time they started looking at the Enterprise Development picture. The prototypes were a success, the new features are being used, it’s time to Robustify. But how?

NoCode Projects in the Real World

It’s been interesting watching how the fact that PaaS offerings limit the available functionality affects an agile project, we’re linking to components running on Amazon Web Services which, being custom built on the IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) platform, are much more flexible. When it came down to the question of securing the endpoints, our Cast Iron Live product offered very few options so we didn’t need to spend long choosing the one we would offer! In contrast, the AWS team became bamboozled with choice and because of this, overran on their deadline to secure interfaces. Hmm. Could this be seen as a benefit of PaaS?

So, on to creating a process. With Cast Iron Live, we were able to create unit tests fairly easily because all of our orchestrations were basically proxying HTTP endpoints. We could reference a mock HTTP endpoint and use a tool like SoapUI or Postman to script the expected result for various edge case scenarios. For instance, one of our orchestrations was exposing a SOAP service functionality as RESTful JSON. For our edge cases we created a mock service that returned each of the possible SOAP faults depending on incoming query parameters, and in our Postman test “scripts” we ensured that the JSON service returned a suitably relevant HTTP response code. We could also emulate and test endpoint timeout scenarios, and mismatching Content-Type headers (for instance, somebody sends in content that they said was application/xml but actually consisted of JSON). The existence of the Cast Iron web interface allowed us to update the endpoint details programmatically so the entire unit test could be scripted.

The other handy thing about Cast Iron is the SOAP service which exposes the admin functionality. So we were able to run a kind of “test driven deployment”, whereby in a program we defined which endpoints and other configuration values we would expect to be referenced in each environment (for example, the production AWS endpoint should only be referenced from the Production Cast Iron environment, all outgoing connections should time out after 15 seconds) and then fix our deployment based on the program outcome. This was also a great opportunity to weave in writing some real code and using Java 8 streams into an otherwise boring project…

Dark Clouds

What’s the most annoying thing about the cloud? The immaturity of many products is certainly annoying. Whilst Cast Iron itself is a mature product, its Live offering certainly seems fairly new - I can’t believe there are that many people using it in anger as we didn’t get too badly shouted at by IBM when we almost brought on a Denial of Service attack by adding the decimal point in the wrong place whilst load-testing our system… and we have had numerous teething problems requiring version upgrades which, of course, we had to rely on IBM to perform. There is a feeling of helplessness attached to PaaS offerings!

Days when the network is slow are not particularly rewarding, either, especially as Cast Iron’s NetBeans-based web interface feels rather dated and prone to cache errors.

For me, it’s the vast array of restrictions that aggravates me – for instance the inability to restart anything at a process level, and the inability to see server and network log files or memory profiles, or even to set up your own test harnesses and have them access your cloud app. In the example above when we were figuring out how to unit test, we had to deploy our mock services to a cloud and make them internet-available so that Cast Iron could see them. No handy installs on localhost for us! The fact that we had to configure our orchestrations to communicate via HTTPS also extremely limited the number of testing services we could use. Here’s a summary of the pages that got us through.

Top Five Cloud API Development Support Sites

- http://httpbin.org - allows HTTPS and even has handy things like an endpoint with a configurable delay so that we could emulate timeouts, but we couldn’t connect to httpbin from Cast Iron Live via HTTPS due to some unfortunate SSL incompatibility.

- http://requestb.in/ - generating a new “bin” will provide you with a unique ID of a “bin” to send requests to. You can then view the requests and headers you have sent.

- http://www.utilities-online.info/xmltojson - when you are converting a SOAP API into a RESTful one, this is great to help define what your JSON will look like

- http://www.freeformatter.com/xsl-transformer.html - testing the parse of your SOAP responses

- http://www.restapitutorial.com/httpstatuscodes.html - translate your SOAP faults to sensible HTTP codes. I love the easy layout of this site. HTTP 418 “I am a Teapot”? Who knew!

Top Tools for Cloud API Development

- Postman (Google Chrome plugin) – HTTP calls with auth support. Easy to install, link it to your Google account and carry it with you everywhere, remembers what you’ve sent if you forget to save it..

- SoapUI from SmartBear – still my favourite SOAP message dispenser, great support for various authentication options, the free option will probably give you everything you need

- Python – the language of choice for our team to knock up a quick script or two – simple HTTP connection interfaces, easy to set up the environment, easy to read the code, easy to set up the runtime environment on a laptop.

- Altova XMLSpy – our team’s vote for the best XML / XSLT / XSD / WSDL editor. Pricey, but apparently worth it!

Get in the Queue

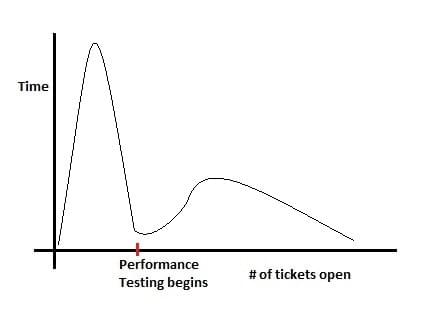

Then there’s the painful world of tickets and service agreements. For a low-level developer who is used to being able to scramble through application and server logs at will, to have to open an online ticket and wait for an SLA to kick in to find out what’s causing your issue is extremely frustrating. It also encourages a slopey-shouldered “it’s the provider’s fault” type of mentality; if you can’t see what you’ve done wrong it’s hard to take ownership for it. You can probably plot the maturity of a PaaS project by looking at the number of tickets open - at the start there will be a proliferation of user-error-type tickets, then all will go quiet, then performance testing will kick in and a small but extremely serious sub-set of tickets will appear.

Even the providers don’t seem to have this process right - with IBM Cast Iron, when we phoned the IBM support call centre they denied all knowledge of the product, and submitting tickets via the support portal has led to two flows of information - one logged on the ticket, and one drifting around in email chains as the reply to an email on a subject does not seem to necessarily make it back to the rest of the ticket info.

In Summary

My conclusion is that PaaS offerings can’t be ignored by developers - we need to assess the total cost of ownership of PaaS apps vs build-your-own, and I think there will often be occasions where it no longer makes financial sense to build. The popularity of IaaS platforms such as AWS means that the argument around owning/managing your own hardware is no longer present in favour of the Build camp, which further evens the playing fields.

If PaaS is going to become a more common occurrence in solution architectures, we need to define a better development process. There is a powerful temptation for companies to associate technology project processes with code, rather than technical architecture - and as such, skip a lot of the important rigours when implementing a PaaS solution. Just because there’s no code doesn’t mean you can’t build a test-driven development and deployment framework, that you can’t script a lot of the required processes. The PaaS selling points are all around speed of solution development, so vendors seldom take the time to remind you to wrap all this speed in some structure. Time to start setting up some guidelines.