Background

Digital Advertising is a form of marketing which uses the Internet to deliver promotional messages to consumers.

In the Digital Advertising ecosystem there are 3 main actors:

- consumers, who are the recipients of the messages

- advertisers, who are the entities willing to spread a specific message about their service or product

- publishers, who own the space to display an advertiser’s message.

Consumers are all of us, people who might be interested in a product, hence the target of the value proposition.

Advertisers can be anything from physical people to brick and mortar shops to gaming companies or big corporations, etc.

Publishers can be website owners interested in selling an area of a web page to display an advertisement, or they can be social networks, search engines or any other entity with a Web presence. Publishers can also act as advertisers and vice versa: think of a website which hosts ad space and at the same time promotes its service or product on other platforms.

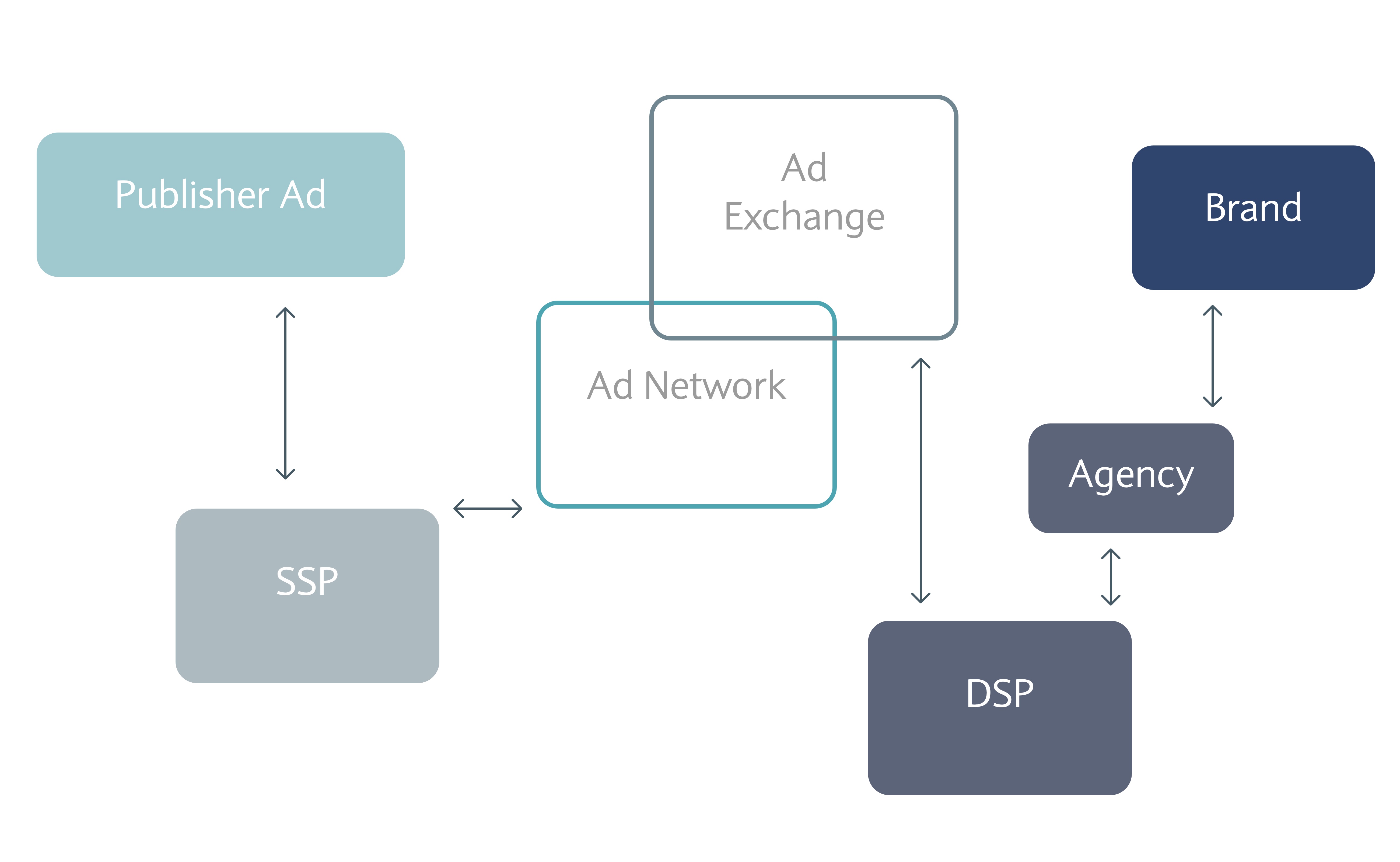

In between publishers and advertisers there are a number of second level entities which make the ad space fulfilment possible. They jointly form the so-called advertising technology (AdTech) stack. Demand Side Platforms (DSPs), Supply Side Platforms (SSPs), Ad Exchanges and Ad Networks form the core of the AdTech stack.

SSPs are platforms enabling publishers to manage, sell and optimize their available inventory. On the opposite side of the spectrum we find DSPs. DSPs allow advertisers working at brands and ad agencies to buy inventory on an impression-by-impression basis from SSPs.

Ad Exchanges are the actual digital marketplaces in between DSPs and SSPs where the purchase of a given ad space happens, typically via real-time bidding (RTB) auctions.

Ad Networks are brokers of inventory and also generally placed between DSPs and SSPs.

The criteria governing the buying and selling of advertising space are not limited to price comparison: advertisers are interested in optimising their investment, which means spending the least for the maximum chance of converting a prospect into a customer.

Such conversion is much more likely if the profile of the buyer persona and the profile of the candidate consumer match. The buyer persona describes the customer archetype. The candidate consumer is also called the “target”. And “targeted advertising” is the first controversial actor of our story.

Targeted advertising is the technique of directing the messaging towards an audience with certain traits, based on the product the advertiser is promoting. These traits can be anything from demographic, to income, to personality, to lifestyle, etc., gathered via many different means, altogether going by the name of “tracking”.

By itself, targeted advertising would not be so bad: doesn’t everyone prefer to be bothered with propositions of products more relevant to their interests rather than not?

The problem is tracking.

Technically, tracking refers to the act of collecting user or device data from a website or a mobile application (commonly referred to as an “app”) and linking it with other data collected from other companies’ apps, websites, or offline properties.

Tracking also refers to sharing the collected data with Data Brokers, which are companies whose primary business is collecting personal information about consumers from a variety of sources and aggregating, analysing, and sharing that information, or information derived from it. Data Brokers are the source of consumers’ profile information, which forms the foundation of advertising digital auctions: whenever a consumer visits a web page hosting an ad, before presenting that same ad, a number of events take place in the AdTech stack, leading to a series of bids to purchase the ad space; such bids are based on the profile of the consumer provided by Data Brokers. It is fair to say though, that not all ad space is sold within the full AdTech stack and hence involving profile information sourced from Data Brokers: there are environments where the stack is squashed into a single platform, think of e.g. the usual suspects Google and Facebook, where advertisers can acquire space directly from them, who in such a case play the role of publishers, SSP, Ad Network… basically the full stack. It is interesting to note that even incumbents like Facebook rely on Data Brokers for profiling: in a report from Forbes

Facebook argues that it must buy this data because that is simply how advertising is done today and that companies want to use the same marketing selectors across every platform.

Coming back to tracking, according to Apple, examples of tracking include:

- Displaying targeted advertisements in your app based on user data collected from apps and websites owned by other companies.

- Sharing device location data or email lists with a data broker.

- Sharing a list of emails, advertising IDs, or other IDs with a third-party advertising network that uses that information to retarget those users in other developers’ apps or to find similar users.

- a third-party SDK in your app that combines user data from your app with user data from other developers’ apps to target advertising or measure advertising efficiency, even if you don’t use the SDK for these purposes. For example, using a login SDK that repurposes the data it collects from your app to enable targeted advertising in other developers’ apps. The following situations are not considered tracking:

- When the data is linked solely on the end-user’s device and is not sent off the device in a way that can identify the end-user or device.

- When the data broker uses the data shared with them solely for fraud detection or prevention or security purposes, and solely on your behalf.

SDKs (Software Development Kits) are third party software components embedded in apps, which implement a large variety of pieces of functionality. Because they’re useful and generally easy to use, SDKs are embedded in lots of the published apps. A comprehensive list and description of the most used SDKs is maintained by MightySignal.

A number of studies from accredited government institutions and news media has brought to the public attention that:

A very large number of apps embed third party SDKs, which form networks that link activity across multiple apps to a single user, and also link to their activities on other devices or mediums like the web. This enables construction of detailed profiles about individuals, which could include inferences about shopping habits, socio-economic class or likely political opinions.

Journal of Economic Literature:

consumers’ ability to make informed decisions about their privacy is severely hindered because consumers are often in a position of imperfect or asymmetric information regarding when their data is collected, for what purposes, and with what consequences.

New York Times, reporting on location tracking:

[the data reviewed] originated from a location data company, one of dozens quietly collecting precise movements using software slipped onto mobile phone apps. […] The companies that collect all this information on your movements justify their business on the basis of three claims: People consent to be tracked, the data is anonymous and the data is secure. None of those claims hold up, based on the file we’ve obtained and our review of company practices. Yes, the location data contains billions of data points with no identifiable information like names or email addresses. But it’s child’s play to connect real names to the dots that appear on the maps. […] Describing location data as anonymous is “a completely false claim” that has been debunked in multiple studies, Paul Ohm, a law professor and privacy researcher at the Georgetown University Law Center, told us. “Really precise, longitudinal geolocation information is absolutely impossible to anonymize.” […] If you have an S.D.K. that’s frequently collecting location data, it is more than likely being resold across the industry,” said Nick Hall, chief executive of the data marketplace company VenPath. […] If a private company is legally collecting location data, they’re free to spread it or share it however they want,” said Calli Schroeder, a lawyer for the privacy and data protection company VeraSafe.

[…] most apps [959,000 apps from the US and UK Google Play stores] contain third party tracking, and the distribution of trackers is long-tailed with several highly dominant trackers accounting for a large portion of the coverage. […] the median number of tracker hosts included in the bytecode of an app was 10. 90.4% of apps included at least one, and 17.9% more than twenty.

The Consumer Council of Norway, following an investigation:

- 20 months after the GDPR has come into effect, consumers are still pervasively tracked and profiled online and have no way of knowing which entities process their data and how to stop them.

- The adtech industry is operating with out of control data sharing and processing, despite that should limit most, if not all, of the practices identified throughout this report.

- The digital marketing and adtech industry has to make comprehensive changes in order to comply with European regulation, and to ensure that they respect consumers’ fundamental rights and freedoms.

In the world of Data Brokers, you have no idea who all has bought, acquired or harvested information about you, what they do with it, who they provide it to, whether it is right or wrong or how much money is being made on your digital identity. Nor do you have the right to demand that they delete their profile on you.

Consequently, government regulators have been taking action by sanctioning those found in breach and by setting rules on personal information handling.

Some of the most notable penalty examples are:

Facebook, Inc. will pay a record-breaking $5 billion penalty [… for] deceiving users about their ability to control the privacy of their personal information.

the FTC [alleged Twitter] used phone numbers and email addresses that were given to the company for safety and security purposes for targeted advertising between 2013 and 2019.

On 21 January 2019, the CNIL’s restricted committee imposed a financial penalty of 50 Million euros against the company Google LLC, in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for lack of transparency, inadequate information and lack of valid consent regarding the ads personalization.

As far as the introduction of data protection regulations is concerned, two of the most prominent examples are the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

CCPA is based on four founding principles, which state that consumers have:

- The right to know about the personal information a business collects about them and how it is used and shared;

- The right to delete personal information collected from them (with some exceptions);

- The right to opt-out of the sale of their personal information; and

- The right to non-discrimination for exercising their CCPA rights.

Similarly, GDPR sets out seven key principles, which lie at the heart of its general data protection regime:

- Lawfulness, fairness and transparency

- Purpose limitation

- Data minimisation

- Accuracy

- Storage limitation

- Integrity and confidentiality (security)

- Accountability

The underlying theme can then be summarised as:

- Reduce consumer data collection to the strictly necessary

- Be transparent on why you need it and on what you do with it

- Be careful of how you handle it, you are accountable for that

Those are basically the same principles adopted by Apple in its approach to privacy.

Privacy on iOS 14

Before iOS 14

Over the years, Apple has distinguished itself for paying special attention to making their products more privacy friendly and helping keeping users’ identity and data more secure.

On Safari, the main feature introduced to hinder tracking is Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP), an initiative started by Apple in 2017.

In the browser context, tracking is achieved historically by third party components (similar to the SDKs described above) dropping small bites of information called cookies in the browser of the consumer. Frequently those cookies carry just one piece of information: a constant identifier assigned to the consumer (or better her/his browser); the rest of the profile is stored in a server which the component communicates directly or indirectly with, via Data Brokers, to incrementally add information, while the consumer visits other sites also embedding the same component.

Back to ITP: Safari started first with blocking third-party cookies, then later on, tightened the noose around client side first-party cookies too, by putting a 7-day expiration date on them. This change was added to iOS 12.2 and Safari 12.1 on macOS High Sierra and Mojave.

First-party cookies are cookies added by the website the consumer is visiting. Placing tracking information in first-party cookies is a workaround recently developed (for good or bad) by some companies to overcome the limitations caused by the blockage of third-party cookies (e.g. Facebook).

More recently, with version 14, released in September 2020, Apple incremented ITP with a “Privacy Report”, listing all trackers Safari detected during the consumer’s site visits.

On the mobile side, Apple introduced the first advertising-related features in 2012, with iOS 6.

First it removed the Unique Device Identifier (UDID), a constant identifier associated to the device, previously always available to apps and playing a role similar to the tracking cookie in the browser context.

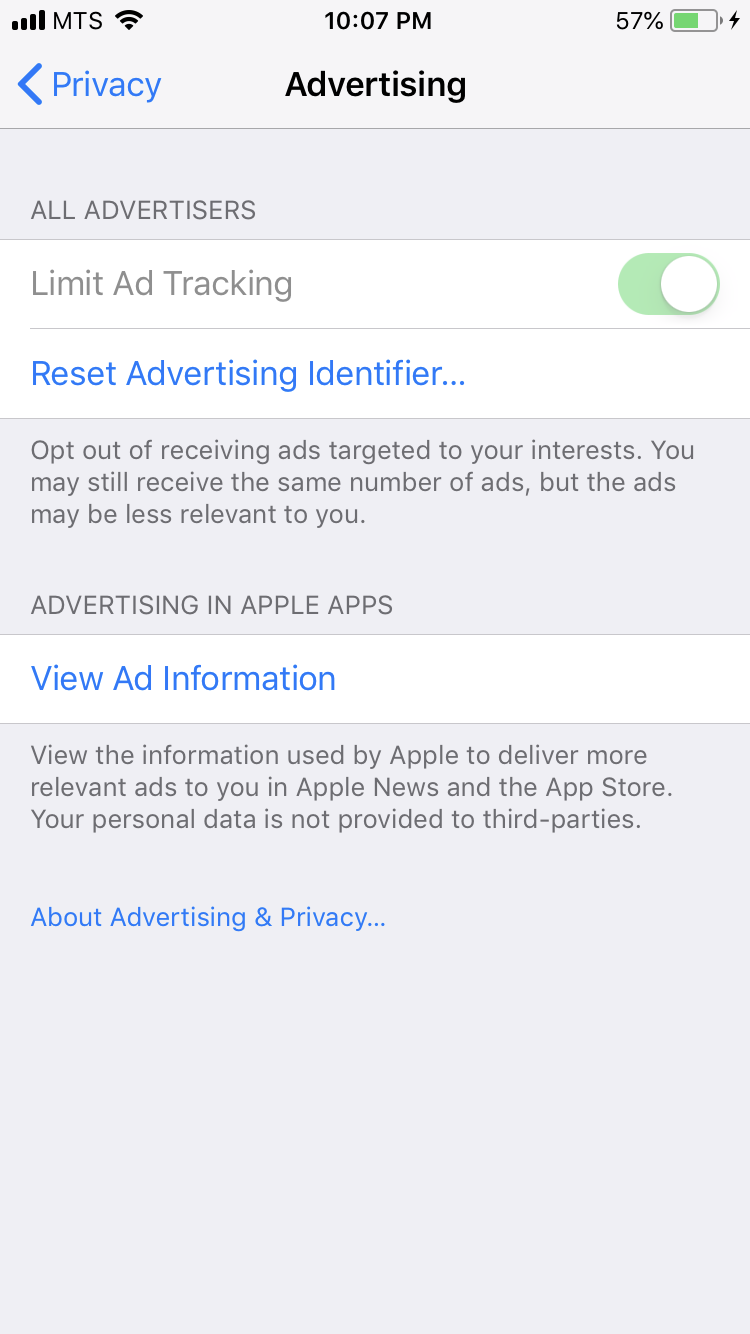

Second, it put in place another device identifier, named Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA), which is a string commonly represented by numbers and letters (technically a 128-bit value, called a UUID). Differently from UDID, the IDFA can be made unavailable to apps if the third new feature is switched on by the user: a feature called Limit Ad Tracking (LAT).

When LAT is enabled, the user’s IDFA is zeroed out (i.e., the value is replaced with zeros) when accessed by apps, hence hiding the device identity.

In reality, prior to iOS 10, the IDFA was still passed, even if a user had enabled LAT, but was accompanied with a request not to use the IDFA. Many companies decided not to honour this request, so Apple decided to zero out the IDFA from iOS 10 onwards.

More recently Apple enabled the users to opt-out of Location-Based Apple Ads: with opt-out disabled, if a user granted the App Store or Apple News access to her/his device location, Apple’s advertising platform would use the current location of the device to provide with geographically targeted ads on the App Store and on Apple News apps.

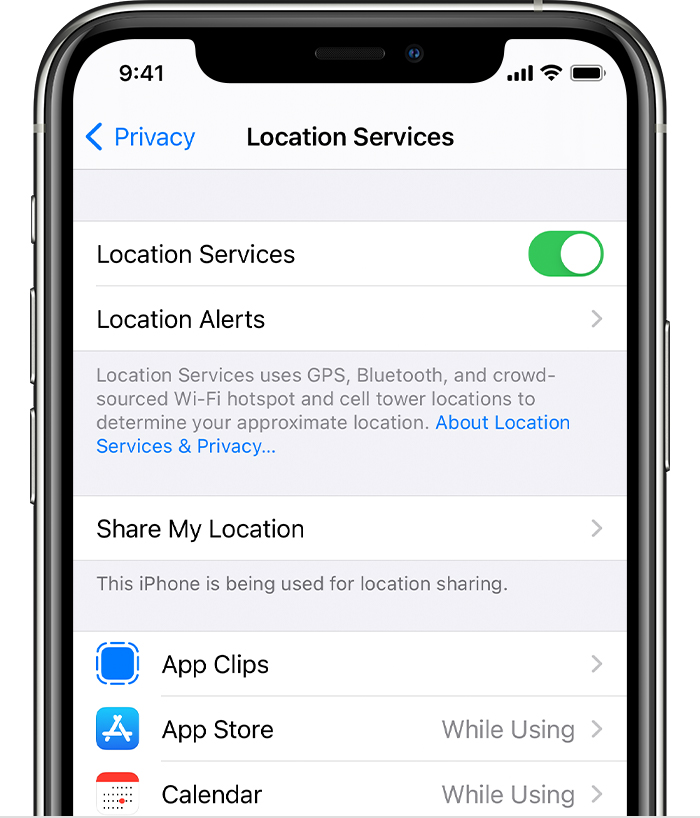

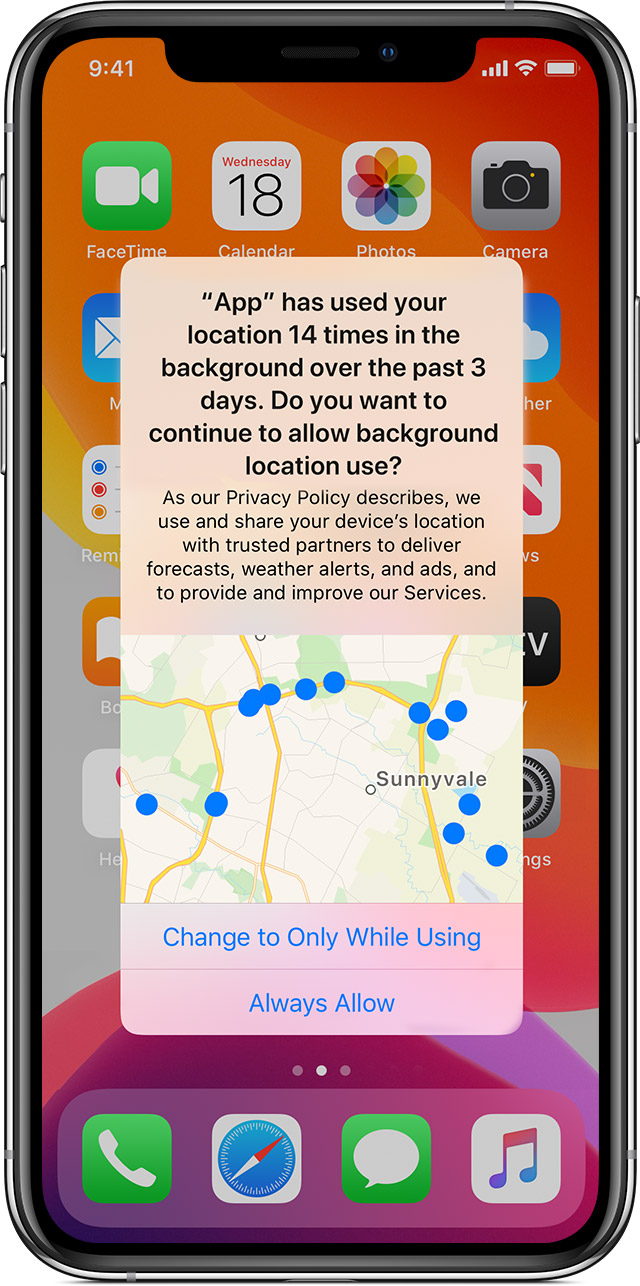

iOS 13 brought with it an update to location data controls.

Firstly, users were periodically shown messages informing them of certain apps that were using their location data in the background (i.e., when not actually using the app in question).

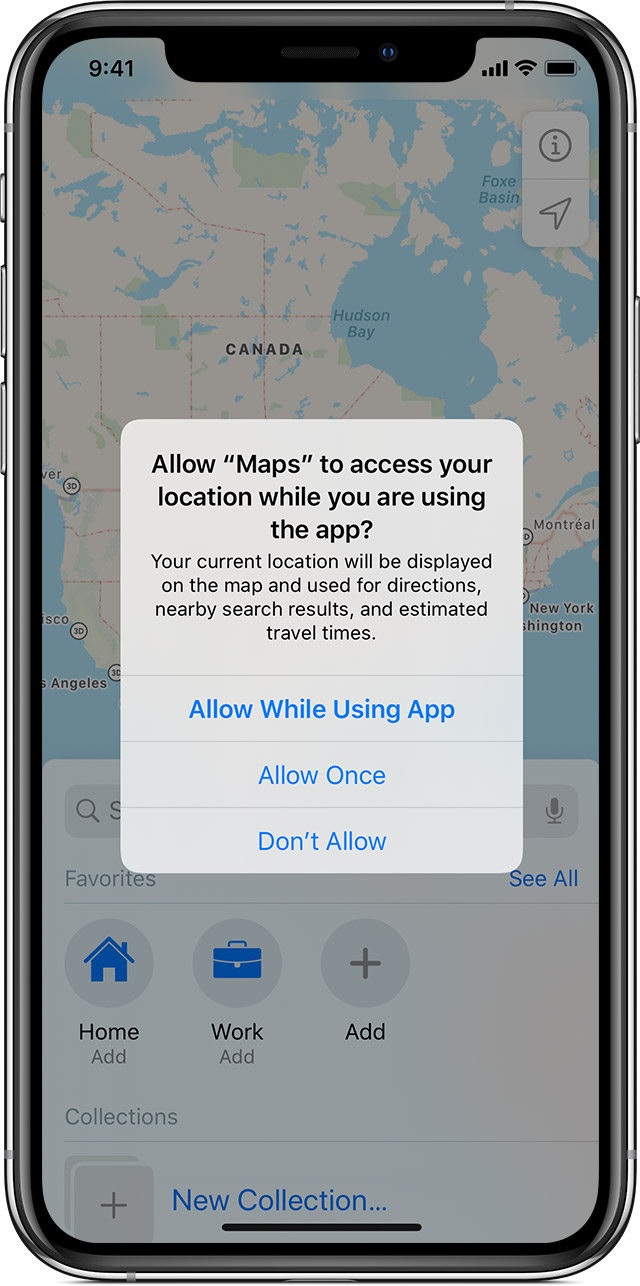

Secondly, Apple changed the options available when users were presented with the popup to choose whether an app could use their location data: the original options were updated from “Always, Never, and While using” to “Allow While Using App, Allow Once, and Don’t Allow”.

Other privacy-related additions to iOS 13 were the permission to use Bluetooth and the permission to read Contacts’ notes: before, apps could access those functionalities freely, while with the new OS, the user was prompted to approve.

That leads us to the present day and to the controverted protagonist of the present perspective: iOS 14 (14.5 in its latest incarnation, Beta released on February the 4th, 2021).

After iOS 14

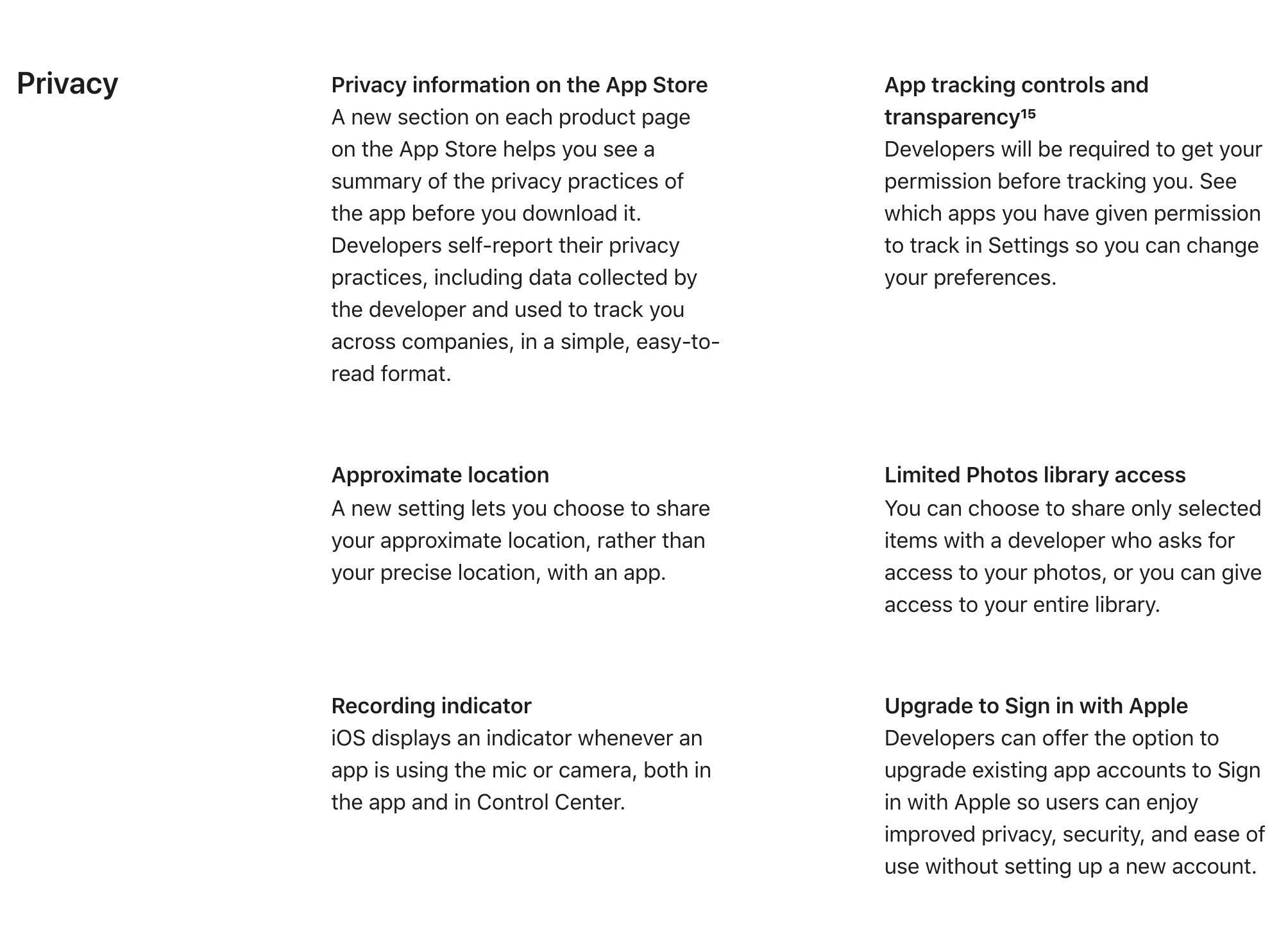

With iOS 14, Apple delivers a number of new privacy-related features:

The most debated ones are the two at the top of the list above: “Privacy information on the App Store” and “App tracking controls and transparency”.

“Privacy information on the App Store” states that in order to submit new apps and app updates, application publishers must provide information about their privacy practices in App Store Connect. If their apps use third-party code, such as advertising or analytics SDK’s, they also need to describe what data the third-party code collects, how the data may be used, and whether the data is used to track users, unless the captured data meets all of the criteria for optional disclosure listed below:

- The data is not used for tracking, which means that the data is not linked with Third-Party Data for advertising or advertising measurement or shared with a data broker.

- The data is not used for Third-Party Advertising, for the app publisher’s Advertising or Marketing purposes, or for Other Purposes

- Collection of the data occurs only in infrequent cases that are not part of the app’s primary functionality, and which are optional for the user.

- The data is provided by the user via the app’s interface, it is clear to the user what data is collected, the user’s name or account name is prominently displayed in the submission form alongside the other data elements being submitted, and the user affirmatively chooses to provide the data for collection each time.

Some data related to apps in the Regulated Financial Services and Health Research can optionally disclose the collected data, provided some extra criteria are met.

In its guidance, Apple also provides definitions for the different types of data, such as “Email Address” and definitions for data use purposes, such as “Third-Party Advertising”, to help app publishers understand what kind of data falls within which policy.

For every type of captured data, Apple requires app publishers to identify if it is linked to the user’s identity (via their account, device, or other details) either by the app publishers themselves or by their partners. Data collected from an app is considered linked to the user’s identity, unless privacy protections are put in place before collection, to anonymize it, such as stripping data of any direct identifiers (e.g., user ID or name) before collection. Additionally, after collection, data must not be linked back to the user’s identity, either directly or tied to other datasets that enable it to be linked indirectly.

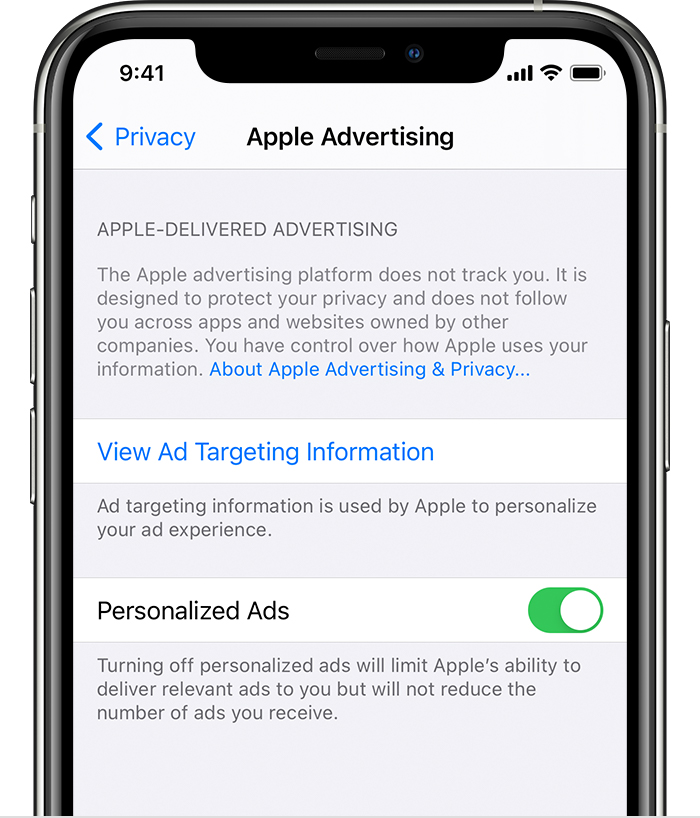

On the second privacy update, “App tracking controls and transparency”: app publishers need to receive the user’s permission through the AppTrackingTransparency framework to

- access the device’s IDFA or

- (in general) track them.

This is the big change: if previously, like seen above, the IDFA was zeroed in case of LAT enabled only, now with iOS 14 (14.5 exactly) it is always so, unless the app receives first the user approval by requesting it via the AppTrackingTransparency framework. Such a request results in the user being presented a popup and prompted to grant the app access to the IDFA. (The popup can be customised with a purpose string to add more information about why the app needs to access the identifier.)

The change will specifically affect the ad targeting side of the ecosystem, in all its declinations: segmentation, retargeting, lookalike audiences, exclusion targeting, etc.

Today in fact, a large number of advertising platforms relies on the IDFA, e.g. the Google Mobile Ads SDK:

The Mobile Ads SDK for iOS utilizes Apple’s advertising identifier

The change goes actually even further than fencing access to the IDFA: from Apple’s FAQ section we understand that the following practices might result in App Store rejection:

- gating functionalities or incentivising the user to grant tracking permission

- using another identifier (e.g., a hashed email address or hashed phone number), unless permission is granted through the AppTrackingTransparency framework

- fingerprinting or using signals from the device to try identifying the device or a user

- tracking performed by an integrated third-party SDK, even in case of single sign-on (SSO) SDK

It is evident then, that any attempt of unexplicitly granted tracking would not be tolerated by Apple and that the app publisher is deemed fully responsible for the code running in her/his app, even for the code running in embedded SDK’s, produced by third parties.

Content providers owning multiple apps and willing to apply analytics across them, have the option to use another ID, the ID for Vendors (IDFV), without obligation to request user’s permission via the AppTrackingTransparency framework. Again though, only in case the IDFV is not combined with other data to track a user across apps and websites owned by other companies. In that case, permission needs still to be granted via the AppTrackingTransparency.

A piece of functionality which is also affected by the privacy changes is “attribution”: whenever an app is installed as a consequence of the user tapping on an advertisement on another app, a common practice today is to leverage the IDFA to detect which ad on which device resulted in the conversion and hence measure the effectiveness of the advertising campaign. Apple guidelines recommend adopting to the SKAdNetwork framework instead, which the AppTrackingTransparency grant is not required for.

In another note Apple announces the upcoming support for Private Click Measurement, that facilitates advertising networks measuring the effectiveness of advertisement clicks within iOS or iPadOS apps that navigate to a website. This might be a welcomed change by the advertising business, considering that the IDFA is not available on the browser, hence tracing the conversion from an ad tapped on mobile and directing to a web page was hard before but possible now.

Conclusion

We have gone through an overview of the main different entities operating in Digital Advertising and how targeted advertising in particular heavily leverage tracking to build up consumer profiles, used to compute likelihood of ad conversions.

We have seen that said profiles are frequently built up by capturing and combining data in opaque ways, which raised concerns amongst public opinion and governments, leading to the introduction of regulations such as GDPR.

In the last part, I presented some of Apple’s efforts to support user privacy in both Safari and iOS, opposing tracking in a similar way as other personal data laws around the world attempt doing. I paid special attention to the latest privacy changes introduced with iOS 14, describing the impact on IDFA usage and App Store publishing process for mobile apps.

I believe that complications for those willing to keep pursuing tracking behind the scenes will be considerable, though possible technical workarounds might be found.

As for those willing to operate in the clear, my recommendation is to apply the updates described in the previous sections.

In summary: treat users with consent, if tracking is needed ask for permission, disclose transparently what will happen to the consumers’ data and why consumers should agree on making it available, give users easy ways to update and change their preferences, keep control of where the acquired data flows, go even further and adopt anonymisation where possible and delete data when not needed anymore.