Background

This post is based on the experience of one project in particular. It is the implementation of a large enterprise solution, primarily to speed up the administration of a contract management process.

The user-based part of the solution is based on a CRM package, but this post is not based on UI-style testing. The bulk of the solution is based on ESB technology - which is the focus of this post.

Continuous Delivery

The project had the aim to set up a full continuous delivery pipeline from the outset. As such it was necessary to choose technologies up-front, with the mindset that they can always be changed later if required.

BDD - Behaviour Driven Development - is a technique for establishing business scenario test specifications in advance of development work. Adding these to the continuous delivery pipeline is ideal to gain fast feedback - especially for guarding against regression.

A “GWT” (Given-When-Then) style syntax for the test specifications was preferred. SpecFlow and NUnit were chosen. This choice was taken quickly rather than thoroughly investigated - mostly based on the experience of a couple of members of the team. NUnit was chosen for the underlying test framework as it appeared to be the most mature of the frameworks SpecFlow can integrate with. I also got the impression most of the team didn’t really care about tests at the time, there were far more “sexier” technology choices to be made!

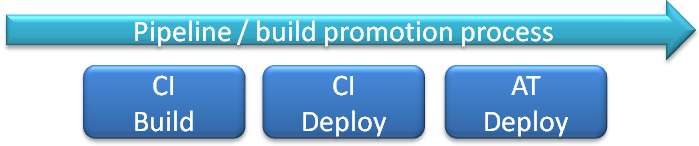

Test specifications were written. It took a while to get these added to the build process. It took even longer to provide an environment in which to run the tests as part of the build process. Eventually this was all fully integrated into the continuous delivery pipeline. This looked something like:

I say “eventually”, in reality it was less than three months from the beginning of development. In the grand scheme of things this was actually pretty good. There were other aspects of the project that required focus and so the continuous delivery pipeline didn’t get the attention it otherwise would have.

Rapid Feedback

The pipeline was set up, the BDD tests were proving continuous feedback on the state of the product. Right?

Reality wasn’t quite so.

Many tests were failing. Many tests were unreliable.

Essentially the tests had been written and tested on developer’s own machines. The tests were running in a different environment, configuration settings needed to be addressed.

The developers of course reacted immediately and fixed all the tests. (Sarcasm. Ed.)

In reality the developers were ignoring the problem. There were far more interesting things to do and the pressure was on from the Product Owner to deliver. The Delivery Manager (lead Agile Coach) insisted no stories would be accepted at the next Sprint Review until these tests were fixed! This bold move ensured the continuous delivery pipeline finally had the attention it needed.

To be fair to the developers, the message from the Delivery Manager was also to the Product Owners to verify the tests. Essentially more and more work was being expected of the developers, but at the expense of quality. Not a sustainable situation.

So the tests were fixed, but that is still not the end of the story. The tests were taking a long time to run, sometimes as long as eight hours. For an overnight run, this isn’t too much of a problem, but it certainly was not in keeping with our vision of “rapid feedback”.

One of the problems with adding BDD tests to the continuous delivery pipeline is that the story with which they are associated may not be complete yet. Across a large team, this could amount to a good few tests, perhaps a dozen or more. So how should the pipeline discriminate between tests that won’t pass (story not yet implemented), tests that should pass (story implementation complete awaiting test verification) and tests that must pass (to detect regression caused by other development work)?

Test Promotion

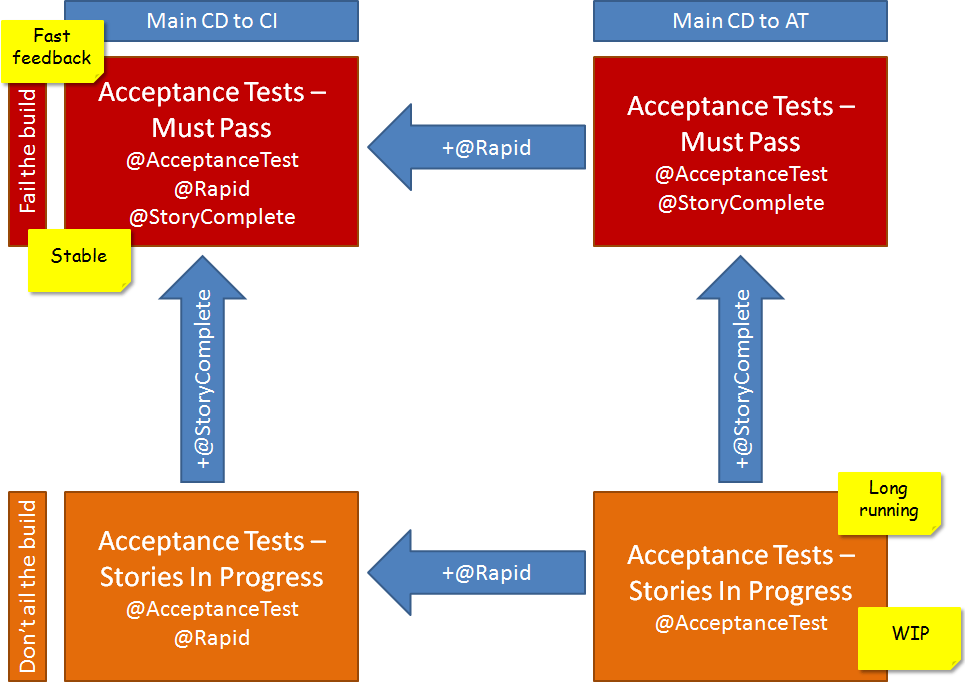

This situation was addressed by re-categorising the tests and putting in place a simple promotion mechanism:

- @AcceptanceTest - tests marked as ready to be added to the continuous delivery pipeline

- @StoryComplete - tests for stories that are deemed “done”

- @Rapid - tests that execute quickly

With the addition of these categories we could improve the feedback given by the builds in the continuous delivery pipeline.

CD to AT

The third step in the pipeline is the “continuous delivery to acceptance test” build. A bit of a mouthful and the naming is historic/convention rather than meaningful: essentially it’s the main build deployed to the Acceptance Testing environment.

This build is scheduled overnight and it doesn’t really matter how long it takes. The purpose of this build is to provide comprehensive coverage, at the expense of frequency of feedback.

The tests are two tests runs: those tests that might pass and tests that must pass. If any of the tests in the latter run fail, the build is marked as failed. The use of the @StoryComplete tag is used to select the “must pass” tests.

The test run usually took between four and eight hours, depending on the number of failures. Since failures were usually due to time-outs in the asynchronous solution, this would result in a much longer execution time.

CD to CI

The second step in the pipeline is the “continuous delivery to continuous integration” build. The main build deployed to the continuous integration environment. Again, not a particularly meaningful name.

This build is a defined as a rolling build. (This a Microsoft Team Foundation Server build server build type definition. Many change-sets are rolled-up together into a build. The next build can be configured to start immediately after the previous has finished or at a specified interval after the previous finished, again with all the change-sets during the interval rolled-up.)

Speed is clearly more important here than for the overnight build. The build was configured to select tests marked with the @Rapid category.

The tests themselves were marked manually with the @Rapid category. Some filtering criteria was used to do this - essentially tests that were passing reliably and executed in under 10 seconds.

This resulted in a build that executed in around thirty minutes (which included the build, deployment, integration tests and acceptance tests). The rolling build was set to sixty minutes so that the build agent wasn’t in continuous use.

Promotion

For the project to receive quicker feedback, the incentive was to improve tests. This way they could be promoted from the daily feedback loop to the hourly feedback loop, far more desirable in seeking “done” against a story.

The pipeline now looks something like:

(Note this is not the full pipeline, there are further steps to deploy to Model Office, Pre-production and Production environments.)

Throughput

The situation was better. A framework had been put in place to get faster feedback. But it’s still not quite the original “vision”.

So how can the speed of the tests be improved?

This has proven to be challenging. The framework executes each test sequentially, one by one. Failures caused the biggest delay and so these needed addressing first. One of the developers started experimenting with a “circuit breaker”, essentially detecting a broken state that would cause multiple tests to fail and so flagging those failures quickly.

But the very nature of the solution means that delays are expected. During the execution of any one test there can be many delays whilst execution happens in the background - essentially dead time as far as the build server is concerned.

But from the point of view of the solution there is little or no benefit to improving the response time of these actions. Scalable architectures are all about throughput, not response time.

Little’s Law

(I have a previous post on the topic of Little’s Law.)

Little’s Law is a mathematical theory of probability in the context of queueing theory:

L = λW

L = number in the system, λ = throughput, W = response time

So since we cannot control the response time, to increase the throughput we have to increase the number in the system. Currently this is fixed to one since the tests run sequentially.

I thought of two approaches to this problem.

Parallel Tests

The obvious solution is to run multiple tests in parallel. After investigation though, it appears it is not possible to do this with the current tooling we have. There are a few limitations, but the biggest is NUnit itself - the test runner.

SpecFlow has a tool called SpecFlow+ Runner. This is a paid-for addition. We’re not against purchasing extra software, but for this aspect of the project we’re trying to avoid tie-in to a particular tool. From the documentation it was also unclear if this tool would definitely help us.

A tool called PNUnit came up. Unfortunately that tool doesn’t really run tests in parallel. What it does is split tests into sets to distribute across many build agents - not really what we are looking for.

Set Tests Running and Collect Results Later

It did occur to me that a better use of our message-driven solution would be to set all the tests running in some asynchronous fashion and then collect all the results later.

Potentially, I thought this to be a very fresh and exciting approach to the problem! It would certainly be very fitting for the asynchronous nature of our solution. Perhaps it would work something like: execute all the “Given”s first, then the “When”s, and finally the “Then”s.

The drawback is it would require some pretty major changes to our tests. How would the context be held between execution of the different steps in the test specification? How would the steps be executed asynchronously? It would also require some changes to the underlying test framework.

Pretty exciting stuff, but too much to take on now. Definitely something I will revisit at a later time though.

New Tooling

During my investigation I kept getting drawn back to NUnit as it does have some asynchronous/parallel features. It turns out these are aimed solely at testing Silverlight applications and are not transferable to other technologies. A Dead-end, or so I thought.

The next major version of NUnit (NUnit 3.0) contains some better features for parallel test execution. At the time of writing it’s still in beta, but it doesn’t look too far off.

I decided to give it a try. I set up some dummy tests against a dummy asynchronous solution using the SpecFlow and NUnit versions we currently use. I then upgraded to NUnit 3.0 and upgraded the VisualStudio test adapter, also NUnit 3.0. This all worked fine, the beta version looks pretty stable and usable.

So now to running the tests in parallel. Currently, the new NUnit framework only allows parallel execution at the “test fixture” level (essentially a test class). Test fixtures are marked with the addition of the following attribute:

NUnit.Framework.Parallelizable(NUnit.Framework.ParallelScope.Fixtures)

Which is simple enough. Except that SpecFlow generates the NUnit test code - so where to put the attribute?

I created a simple SpecFlow plug-in to add the attribute. The creation of the plug-in and the syntax of adding the attribute is a bit fiddly, but it worked! I was then able to run tests in parallel!

I haven’t actually tried this out on the project code-base yet, but I hope to do so in the coming weeks. The plug-in requires a bit more refinement, but the principle is there. I also have a slight reservation in that on the build server it turns out the tests aren’t actually executed by NUnit - apparently VSTest intercepts and runs them, though I don’t see this as an insurmountable problem.

Conclusion

To gain rapid feedback from BDD tests against an asynchronous solution requires extra thought. The weakness appears to be the test runners, they are not geared towards asynchronous processing.

In the first instance you may well need to make a compromise on speed and coverage. Tests that are fairly fast can be executed often, slower tests can be run overnight.

Running tests in parallel may bring about an improvement, but ultimately test runner architecture must evolve if they are to be suited to a asynchronous solutions. The idea of triggering the tests then collecting the results later is potentially quite powerful for this.

I’ll follow up with another post when I do try it out.

I would be very interested to hear any war stories, insights or similar problems you may have encountered, please submit a comment to start the conversation.

I’ve uploaded the source code, the proof-of-concept BDD-Parallel and the SpecFlow plugin ParallelAttributePlugin.