During my journey into microservices, it has become apparent that the majority of online sample/howto posts regarding implementation focus solely on REST as a means for microservices to communicate with each other. Because of this, you could be forgiven for thinking that RESTful microservices are the de facto standard, and the approach to strive for when designing and implementing a microservices-based system. This is not necessarily the case.

REST

The reason why REST based microservices examples are most popular is more than likely due to their simplicity; services communicate directly and synchronously with each other over HTTP, without the need for any additional infrastructure.

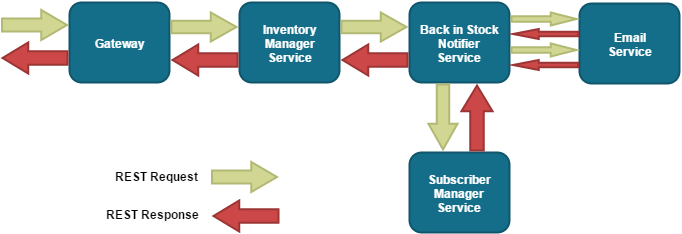

As an example consider a system that notifies customers when a particular item is back in stock. This could be implemented via RESTful microservices as so:

- An external entity sends an inventory update request to a REST gateway address.

- The gateway forwards this request to the Inventory Manager Service.

- The Inventory Manager updates the inventory based on the request it receives, and subsequently sends a request to the Back in Stock Notifier.

- The Back in Stock Notifier sends a request to the Subscriber Manager, requesting all users that have registered to be notified when the item is back in stock.

- It then emails each in turn, by sending an email REST request to the Email Service for each user.

- Each service then responds in turn, unwinding back to the gateway and subsequently to the client.

It should be noted that although communication is point-to-point, hard coding services addresses would be a very bad design choice, and goes against the very fundamentals of microservices. Instead a Service Discovery mechanism should be used, such as Eureka or Consul, where services register their API availability with a central server, and clients to request a specific API address from this server.

Diving deeper, there are a number of fundamental flaws or things to consider in this implementation:

Blocking

Due to the synchronous nature of REST, the update stock operation will not return until the notification service has completed its task of notifying all relevant customers. Imagine the effect of this if a particular item is very popular, with 1000s of customers wishing to be notified of the additional stock. Performance could potentially be severely affected and the scalability of the system will be hindered.

Coupling and Single Responsibility

The knowledge that ‘when an item is back in stock, customers should be notified’ is ingrained into the inventory manager service but I would argue that this should not be the case. The single responsibility of this service should be to update system inventory (the inventory aggregate root) and nothing else. In fact, it should not even need to know about the existence of the notification service at all. The two services are tightly coupled in this model.

When Services go Pop

Services WILL fail, and a microservice based system should continue to function as well as possible during these situations. Due to the tightly coupled system described above, there needs to be a failure strategy within the Inventory Manager (for example) to deal with the scenario where the Back in Stock Notifier is not available. Should the inventory update fail? Should the service retry? It is also vital that the request to the Notifier fails as quickly as possible, something that the circuit breaker pattern (e.g. Hystrix) can help with. Even though failure scenarios will have to be handled regardless of the communication method, bundling all this logic into the calling service will add bloat. Coming back to the single-responsibility issue, again it’s my opinion that the Inventory Manager should not be responsible for dealing with the case where the Notifier goes dark.

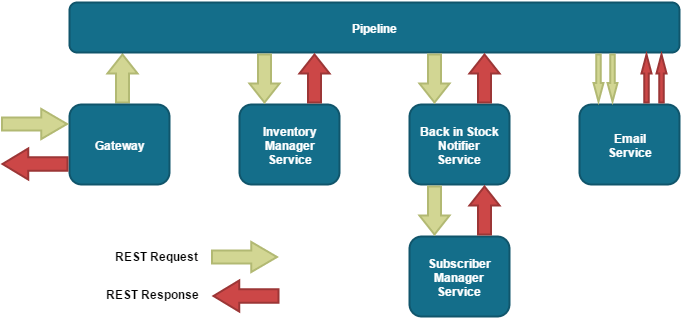

Pipelines

One way to overcome the coupling of services and to move the responsibility of routing away from a microservice is to follow the pipeline enterprise pattern. Our subsystem would now look like this:

Communication may still be REST based, but is no longer ‘point-to-point’; it is now the responsibility of the pipeline entity to orchestrate the data flows, rather than the services themselves. Whilst this overcomes the coupling issue (and blocking with a bit more work, via asynchronous pipelines), it is considered good practice within the microservices community to strive for services that are as autonomous and coherent as possible. With this approach, the services must rely on a third party entity (the pipeline orchestrator) in order to function as a system and are therefore not particularly self sufficient.

For example, notice that the pipeline will receive a single response from the Back in Stock Notifier (even though there are 2 subscribers), but must be configured in such a way that it can parse the response so that it can subsequently send individual “send email” requests to the Email Notifier for each subscriber. It could be argued that the Email Sender could be modified to batch send emails to many different subscribers via a single request, but if for example, each users name must be included in the email body, then there would have to be some kind of token replace functionality. This introduces additional behavioural coupling, where the Notifier has specific knowledge about the behaviour of the Email Sender.

Asynchronous Messaging

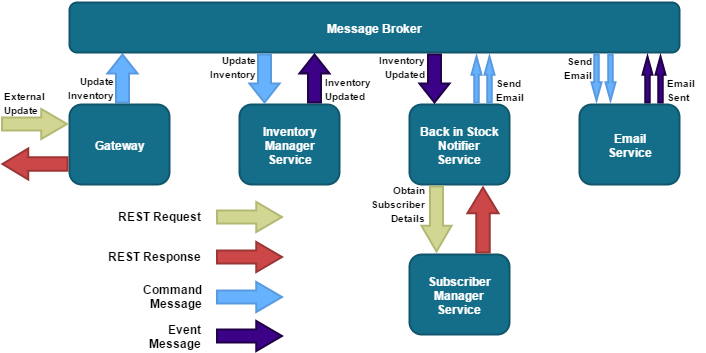

In a messaging based system, both the input and output from services are defined as either commands or events. Each service subscribes to the events that it is interested in consuming, and then receives these events reliably via a mechanism such as a messaging queue/broker, when the events are placed on the queue by other services.

Following this approach, the stock notification subsystem could now be remodelled as follows:

Cohesion is obtained via a shared knowledge of queue names, and a consistent and well known command/event format; an event or command fired by one service should be able to be consumed by the subscriber services. In this architecture, a great deal of flexibility, service isolation and autonomy is achieved.

The Inventory Manager for instance, has a single responsibility, updating the inventory, and is not concerned with any other services that are triggered once it has performed its task. Therefore, additional services can be added that consume Inventory Updated events without having to modify the Inventory Manager Service, or any pipeline orchestrator.

Also, it really doesn’t care (or have any knowledge of) if the Back in Stock Notifier has died a horrible death; the inventory has been updated so it’s a job well done, as far as the Inventory Manager is concerned. This obliviousness of failure from the Inventory Manager service is actually a good thing; we MUST still have a strategy for dealing with the Back in Stock Notifier failure scenario, but as I have stated previously, it could be argued that this is not the responsibility of the Inventory Manager itself.

This ability to deal with change such as adding, removing or modifying services without affecting the operation or code of other services, along with gracefully handling stressors such as service failure, are two of the most important things to consider when designing a microservices based system.

Everything in the world of asynchronous messaging isn’t entirely rosy however, and there are still a few pitfalls to consider:

Design / Implementation/ Configuration Difficulty

The programming model is generally more complex in an asynchronous system compared to a synchronous counterpart, making it more difficult to design and implement. This is because there are a number of additional issues that may have to be overcome, such as message ordering, repeat messages and message idempotency.

Also, the configuration of the message broker will also need some thought. For example, if there are multiple instances of the same service, should a message be delivered to both of the services or just one? There are use cases for both scenarios.

The Very Nature of Asynchronous Messages

The fact that the result of an action is not returned immediately can also increase the complexity of system and user interface design and in some scenarios it does not even make logical sense for a subset of a system to function in an asynchronous manner. Take the Back in Stock Notifier for example, and its relationship with the Subscriber Manager; it is impossible for the notifier to function without information about the subscribers that it should be notifying, and therefore a synchronous REST call makes sense in this case. This differs from the email sending task, as there is no need for emails to be sent immediately.

Visibility of Message Flow

Due to the dispersed and autonomous nature of messaging based microservices, it can be difficult to fully get a clear view of the flow of messages within the system. This can make debugging more difficult, and compared to the pipeline approach, the business logic of the system is harder to manage.

Note: Event based messaging can expanded even further by applying event-sourcing and CQRS patterns, but this is beyond the scope of this article. See the further reading links for more information.

So which communication approach is best when designing your microservices? As with most things in software development (and life??), it depends on the requirements! If a microservice has a real need to respond synchronously, or if it needs to receive a response synchronously itself, then REST may well be the approach that you would want to take. If an enterprise requires the message flow through the system to be easily monitored and audited, or if it’s considered beneficial to be able to modify and view the flow through the system from one centralised place, then consider a pipeline. However, the loosely coupled, highly scalable nature of asynchronous messaging based systems fits well with the overall ethos of microservices. More often than not, despite some significant design and implementation hurdles, an event based messaging approach would be a good choice when deciding upon a default communication mechanism in a microservices based system.

Further Reading

- Netflix OSS - The home of Eureka and Hystrix

- Consul

- Antifragile Software - By Russ Miles

- Event Sourcing - By Martin Fowler

- Building and Deploying Microservices with Event Sourcing, CQRS and Docker - By Chris Richardson