In a previous article on this blog, I talked about why code review is a good idea, and some aspects of how to conduct them. This time I want to dig deeper into the practicalities of reviewing code, and mention a few things to watch out for.

Code review is the first line of defence against hackers and bugs. When you approve a pull request, you’re putting your name to it - taking a share of responsibility for the change.

Once bad code has got into a system, it can be difficult to remove. Trying to find problems in an existing codebase is like looking for an unknown number of needles in a haystack, but when you’re reviewing a pull request it’s more like looking in a handful of hay. The difficult part is recognising a needle when you see one. Hopefully this article will help you with that.

Code review shouldn’t be a box-ticking exercise, but it can be helpful to have a list of common issues to watch out for. As well as the important question of whether the change will actually work, the main areas to consider are:

- Security

- Performance

- Accessibility

- Maintainability

I’ll touch on these areas in more detail - I’ll be talking about Drupal and PHP in particular, but a lot of the points I’ll make are relevant to other languages and frameworks.

Security

I don’t claim to be an expert on security, and often count myself lucky that I work in what my colleague Andrew Harmel-Law calls “a creative-inventive market, not a safety-critical one”.

Having said that, there are a few common things to keep an eye out for, and developers should be aware of the OWASP top ten list of vulnerabilities. When working with Drupal, you should bear in mind the Drupal security team’s advice for writing secure code. For me, the most important points to consider are:

Does the code accept user input without proper sanitisation?

In short - don’t trust user input. The big attack vectors like XSS and SQL injection are based on malicious text strings. Drupal provides several types of text filtering - the appropriate filter depends on what you’re going to do with the data, but you should always run user input through some kind of sanitisation.

Are we storing sensitive data anywhere we shouldn’t be?

Security isn’t just about stopping bad guys getting in where they shouldn’t. Think about what kind of data you have, and what you’re doing with it. Make sure that you’re not logging people’s private data inappropriately, or passing it across network in a way you shouldn’t. Even if the site you’re working on doesn’t have anything as sensitive as the Panama papers, you have a legal, professional, and personal responsibility to make sure that you’re handling data properly.

Performance

When we’re considering code changes, we should always think about what impact they will have on the end user, not least in terms of how quickly a site will load. As Google recently reminded us, page load speed is vital for user engagement. Slow, bloated websites cost money, both in terms of mobile data charges and lost revenue.

Does the change break caching?

Most Drupal performance strategies will talk about the value of caching. The aim of the game is to reduce the amount of work that your web server does. Ideally, the web server won’t do any work for a page request from an anonymous user - the whole thing will be handled by a reverse proxy cache, such as Varnish. If the request needs to go to the web server, we want as much of the page as possible to be served from an object cache such as Redis or Memcached, to minimise the number of database queries needed to render the page.

Are there any unnecessary uses of $_SESSION?

Typically, reverse proxy servers like Varnish will not cache pages for authenticated users. If the browser has a session, the request won’t be served by Varnish, but by the web server.

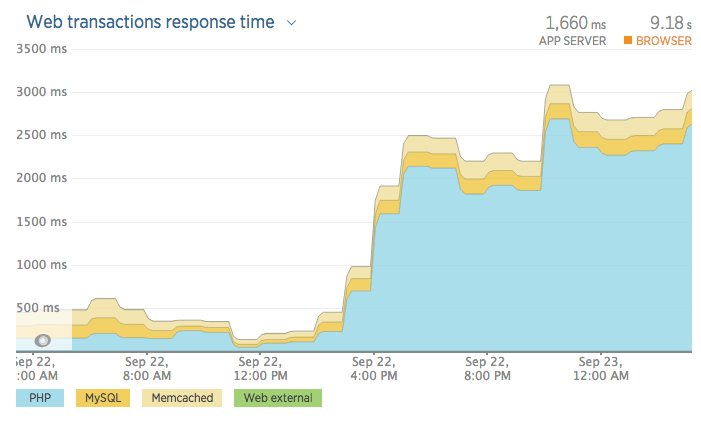

Here’s an illustration of why this is so important. This graph shows the difference in response time on a load test environment following a deployment that included some code to create sessions. There were some other changes that impacted performance, but this was the big one. As you can see, overall response time increased six-fold, with the biggest increase in the time spent by the web server processing PHP (the blue sections on the graphs), mainly because a few lines of code creating sessions had slipped through the net.

Are there any inefficient loops?

The developers’ maxims “Don’t Repeat Yourself” and “Keep It Simple Stupid” apply to servers as well. If the server is doing work to render a page, we don’t want that work to be repeated or overly complex.

What’s the front end performance impact?

There’s no substitute for actually testing, but there are a few things that you can keep an eye out for when reviewing change. Does the change introduce any additional HTTP requests? Perhaps they could be avoided by using sprites or icon fonts. Have any images been optimised? Are you making any repeated DOM queries?

Accessibility

Even if you’re not an expert on accessibility, and don’t know ARIA roles, you can at least bear in mind a few general pointers. When it comes to testing, there’s a good checklist from the Accessibility Project, but here are some things I always try to think about when reviewing a pull request.

Will it work on a keyboard / screen reader / other input or output device ?

Doing proper accessibility testing is difficult, and you may not have access to assistive technology, but a good rule of thumb is that if you can navigate using only a keyboard, it will probably work for someone using one of the myriad input devices. Testing is the only way to be certain, but here are a couple of simple things to remember when reviewing CSS changes: hover and focus should usually go together, and you should almost never use outline: none;.

Are you hiding content appropriately?

One piece of low-hanging fruit is to make sure that text is available to screen readers and other assistive technology. Any time I see display: none; in a pull request, alarm bells start ringing. It’s usually not the right way to hide content.

Maintainability

Hopefully the system you’re working on will last for a long time. People will have to work on it in the future. You should try to make life easier for those people, not least because you’ll probably be one of them.

Reinventing the wheel

Are you writing more code than you need to? It may well be that the problem you’re looking at has already been solved, and one of the great things about open source is that you’re able to recruit an army of developers and testers you may never meet. Is there already a module for that?

On the other hand, even if there is an existing module, it might not always make sense to use it. Perhaps the contributed module provides more flexibility than our project will ever need, at a performance cost. Maybe it gives us 90% of what we want, but would force us to do things in a certain way that would make it difficult to get the final 10%. Perhaps it isn’t in a very healthy state - if so, perhaps you could fix it up and contribute your fixes back to the community, as I did on a recent project.

If you’re writing a custom module to solve a very specific problem, could it be made more generic and contributed to the community? A couple of examples of this from the Capgemini team are Stomp and Route.

One of the jobs of the code reviewer is to help draw the appropriate line between the generic and the specific. If you’re reviewing custom code, think about whether there’s prior art. If the pull request includes community-contributed code, you should still review it. Don’t assume that it’s perfect, just because someone’s given it away for nothing.

Appropriate API usage

Is your team using your chosen frameworks as they were intended? If you see someone writing a custom function to solve a problem that’s already been solved, maybe you need to share a link to the API docs for the existing solution.

Introducing notices and errors

If your logs are littered with notices about undefined variables or array indexes, not only are you likely to be suffering a performance hit from the logging, but it’s much harder to separate the signal from the noise when you’re trying to investigate something.

Browser support

Remember that sometimes, it’s good to be boring. As a reviewer, one of your jobs is to stop your colleagues from getting carried away with shiny new features like ES6, or CSS variables. Tools like Can I Use are really useful in being able to check what’s going to work in the browsers that you care about.

Code smells

Sometimes, code seems wrong. As I learned from Larry Garfield’s excellent presentation on code smells at the first Drupalcon I went to, code smells are indications of things that might be a deeper problem. Rather than re-hash the points Larry made, I’d recommend reading his slides, but it is worth highlighting some of the anti-patterns he discusses.

Functions or objects that do more than one thing

A function should have a function. Not two functions, or three. If an appropriate comment or function name includes “and”, it’s a sign you should be splitting the function up.

Functions that sometimes do different things

Another bad sign is the word “or” in the comment. Functions should always do the same thing.

Excessive complexity

Long functions are usually a sign that you might want to think about refactoring. They tend to be an indicator that the code is more complex than it needs to be. The level of complexity can be measured, but you don’t need a tool to tell you that if a function doesn’t fit on a screen, it’ll be difficult to debug.

Not being testable

Even if functions are simple enough to write tests for, do they depend on a whole system? In other words, can they be genuinely unit tested?

Lack of documentation

There’s more to be said on the subject of code comments than I can go into here, but suffice to say code should have useful, meaningful comments to help future maintainers understand it.

Tight coupling

Modules should be modular. If two parts of a system need to interact, they should have a clearly defined and documented interface.

Impurity

Side effects and global variables should generally be avoided.

Sensible naming

Is the purpose of a function or variable obvious from the name? I don’t want to rehash old jokes, but naming things is difficult, and it is important.

Commented-out code

Why would you comment out lines of code? If you don’t need it, delete it. The beauty of version control is that you can go back in time to see what code used to be there. As long as you write a good commit message, it’ll be easy enough to find. If you think that you might need it later, put it behind a feature toggle so that the functionality can be enabled without a code release.

Specificity

In CSS, IDs and !important are the big code smells for me. They’re a bad sign that a specificity arms race has begun. Even if you aren’t going to go all the way with a system like BEM or SMACSS, it’s a good idea to keep specificity as low as possible. The excellent articles on CSS specificity by Harry Roberts and Chris Coyier are good starting points for learning more.

Standards

It’s important to follow coding standards. The point of this isn’t to get some imaginary Scout badge - code that follows standards is easier to read, which makes it easier to understand, and by extension easier to maintain. In addition, if you have your IDE set up right, it can warn you of possible problems, but those warnings will only be manageable if you keep your code clean.

Deployability

Will your changes be available in environments built by Continuous Integration? Do you need to set default values of variables which may need overriding for different environments? Just as your functions should be testable, so should your configuration changes. As far as possible, aim to make everything repeatable and automatable - if a release needs any manual changes it’s a sign that your team may need to be thinking with more of a DevOps mindset.

Keep Your Eyes On The Prize

With all this talk of coding style and standards, don’t get distracted by trivialities - it is worth caring about things like whitespace and variable naming, but remember that it’s much more important to think about whether the code actually does what it is supposed to. The trouble is that our eyes tend to fixate on those sort of things, and they cause unnecessary cognitive load.

Pre-commit hooks can help to catch coding standards violations so that reviewers don’t need to waste their time commenting on them. If you’re on a big project, it will almost certainly be worth investing some time in integrating your CI server and your code review tool, and automating checks for issues like code style, unit tests, mess detection - in short, all the things that a computer is better at spotting than humans are.

Does the code actually solve the problem you want it to? Rather than just looking at the code, spend a couple of minutes reading the ticket that it is associated with - has the developer understood the requirements properly? Have they approached the issue appropriately? If you’re not sure about the change, check out the branch locally and test it in your development environment.

Even if there’s nothing wrong with the suggested change, maybe there’s a better way of doing it. The whole point of code review is to share the benefit of the team’s various experiences, get extra eyes on the problem, and hopefully make the end product better.

I hope that this has been useful for you, and if there’s anything you think I’ve missed, please let me know via the comments.