Code that relies on timers is tricky to unit test. You have to check the functionality of your code and ensure there is the correct synchronisation between the test and the timer thread.

Unless special measures are taken, exceptions thrown from production code will be swallowed by the timer thread and when this happens the unit test fails with an ambiguous failure (usually a time-out or failed mock expectation).

You can be left in a situation where you have to choose between conservatively long time out values (that make your tests run slowly) or faster unreliable tests that have occasional failures.

Recently I’ve adopted a technique for dealing with these issues, by splitting the functional responsibilities of a class from its timing, so I can test them in isolation.

The HouseKeeper

As an example, imagine you’ve got a HouseKeeper class that removes all the old transactions from a system. It uses a timer to trigger this behaviour every ten minutes. It might look something like this in Java 8:

class HouseKeeper {

private static final long NO_INITIAL_DELAY = 0;

private static final Duration ONE_DAY = Duration.ofDays(1);

private final Transactions transactions;

private final ScheduledExecutorService timerService = Executors.newSingleThreadScheduledExecutor();

public HouseKeeper(Transactions transactions) {

this.transactions = transactions;

}

public void start() {

timerService.scheduleAtFixedRate(

() -> deleteOldTransactions(),

NO_INITIAL_DELAY,

10, TimeUnit.MINUTES);

}

private void deleteOldTransactions() {

transactions.remove(oldTransactions());

}

private Stream<Transaction> oldTransactions() {

final Instant oneDayAgo = Instant.now().minus(ONE_DAY);

return transactions.stream().filter(t -> t.isOlderThan(oneDayAgo));

}

public void stop() {

timerService.shutdown();

}

}

How do you go about testing this? You certainly don’t want your tests to have to wait 10 minutes each time they start the HouseKeeper, before checking if the class removed any transactions.

You could make the timer duration configurable so that the unit test can reduce the timer period to something much shorter.

class HouseKeeper {

...

private final long period;

private final TimeUnit periodTimeUnit;

public HouseKeeper(Transactions transactions, long period, TimeUnit periodTimeUnit) {

...

this.period = period;

this.periodTimeUnit = periodTimeUnit;

}

public void start() {

timerService.scheduleAtFixedRate(

()-> deleteOldTransactions(),

NO_INITIAL_DELAY,

period, periodTimeUnit);

}

...

}

Now you can write a unit test that reduces the timer period to something more manageable and waits long enough for it to trigger.

public class AHouseKeeper {

private static final long ONE_SECOND = 1000;

@Test

public void deletesOldTransactionsPeriodically() throws InterruptedException {

Transactions transactions = one(oldTransaction());

HouseKeeper houseKeeper = new HouseKeeper(

transactions,

500, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

houseKeeper.start();

Thread.sleep(ONE_SECOND);

houseKeeper.stop();

assertEquals(0, transactions.count());

}

private Transaction oldTransaction() {

return new Transaction(Instant.now().minus(Duration.ofDays(2)));

}

private Transactions one(Transaction transaction)

{

Transactions result = new Transactions();

result.add(transaction);

return result;

}

}

This works, but it’s fragile because its based on timing. External factors like the load on the PC will affect when exactly the timer triggers and when the test fails it will be hard to see the cause of the failure (did the code fail or did we not wait long enough).

In addition, the wait slows the test suite down. You can probably tolerate a one second pause in the tests, but as you add more tests that rely on the HouseKeeper those pauses will soon add up.

Controlling Time

Instead of these slow or unreliable tests you could do something different. Let’s create a Clock interface that you can use to represent different types of timers.

interface Clock {

void register(Listener listener);

void start();

void stop();

interface Listener {

void timeElapsed();

}

}

You now update the HouseKeeper class to use an instance of this interface that is passed to its constructor.

public class HouseKeeper {

...

private final Clock clock;

public HouseKeeper(Transactions transactions, Clock clock) {

this.transactions = transactions;

this.clock = clock;

clock.register(() -> deleteOldTransactions());

}

public void start() {

clock.start();

}

...

public void stop() {

clock.stop();

}

}

The rest of the production code will supply the HouseKeeper class with an implementation of this interface that works just like before.

class RealClock implements Clock {

private final long period;

private final TimeUnit periodTimeUnit;

private final List<Listener> listeners = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<>());

private final ScheduledExecutorService timerService = Executors.newSingleThreadScheduledExecutor();

public RealClock(long period, TimeUnit periodTimeUnit) {

this.period = period;

this.periodTimeUnit = periodTimeUnit;

}

@Override

public void register(Listener listener) {

listeners.add(listener);

}

@Override

public void start() {

timerService.scheduleAtFixedRate(this::reportTimeElapse, period, period, periodTimeUnit);

}

private void reportTimeElapse() {

listeners.forEach(Listener::timeElapsed);

}

@Override

public void stop() {

timerService.shutdown();

}

}

Now you can test the HouseKeeper class using a new implementation of Clock that lets you control when the time period elapses.

class ManualClock implements Clock {

private final List<Listener> listeners = new ArrayList<>();

@Override

public void register(Listener listener) {

listeners.add(listener);

}

@Override

public void start() {

// Ignored

}

@Override

public void stop() {

// Ignored

}

public void elapseTime(){

listeners.forEach(Listener::timeElapsed);

}

}

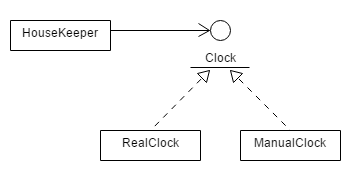

Here’s the overall picture.

The unit test now looks like this.

public class AHouseKeeper {

@Test

public void deletesOldTransactionsPeriodically() {

Transactions transactions = new Transactions();

transactions.add(oldTransaction());

ManualClock clock = new ManualClock();

HouseKeeper houseKeeper = new HouseKeeper(transactions, clock);

houseKeeper.start();

clock.elapseTime();

houseKeeper.stop();

assertEquals(0, transactions.count());

}

...

}

The Thread.sleep has gone so there’s no waiting around and the test is fast. More importantly, there’s no timer thread being run so if the test fails it must be because the functionality is wrong. Finally, any exceptions thrown from the HouseKeeper will be visible to the unit test, making debugging errors easier.

Of course, you’ll still want to exercise the timer set up code inside your integration and stress tests, but you can go forwards with confidence in the code’s core functionality.