Confession time: I find pair programming hugely useful, productive, informative - and draining. Like many developers of my acquaintance, I’m an introvert; which doesn’t mean I don’t like people, just that I am less than enthused about spending hours at a time with them. So pair programming could have been designed as a particularly insidious torture. Like a cliché fantasy maze, it hides its treasures while forcing you to engage with a situation you’d really prefer to avoid.

However, I’m not just a developer. [I’m a real boy! – Ed.] I’m also a practitioner of the traditional Japanese martial art called jujitsu. (For quibbles about the spelling of jujitsu I refer you to the response given in the case Arkell vs. Pressdram.) And in the course of my 15 years of training and teaching jujitsu, I’ve learned a number of attitudes to self-development and the acquisition and improvement of skill that I’ve recently realised could be usefully applied to making pair programming less of an ordeal. I hope you find them useful.

- Lesson the first: everyone has something to teach

- Lesson the second: If you compete instead of collaborating, the end result can suffer

- Lesson the third: dwelling on mistakes is counter-productive

- Lesson the fourth: repetition is the only path to instinctive ability

- Lesson the fifth: if you can’t explain something in a few different ways, you don’t really understand it

- Lesson the sixth: talking is no substitute for doing

- Lesson the seventh: calm is not the same as slow

Let’s look at each of those in turn. Some are related to each other, sometimes in subtle ways.

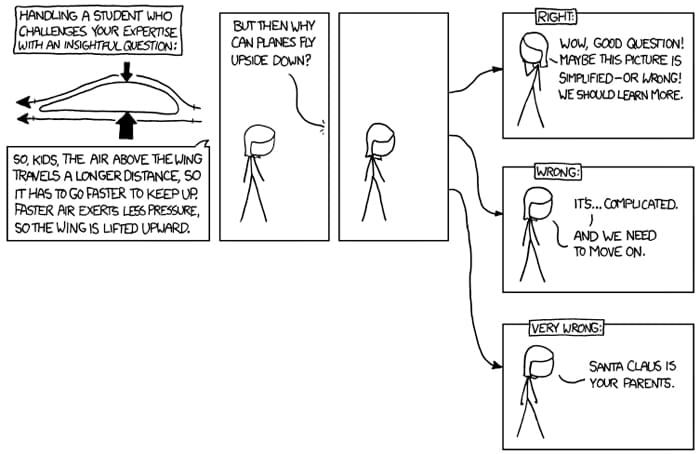

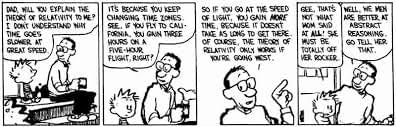

Everyone has something to teach

© xkcd.com

© xkcd.com

A teacher is one who makes himself progressively unnecessary. Thomas Carruthers

This is more subtle a point than it might appear at first. There is the obvious meaning, that there are tips and tricks about programming; about particular coding habits; and about the peculiarities of specific IDEs that I can learn from anyone, however experienced or not they might happen to be. It is also clear, however, that everyone has an individual worldview that they bring to bear on problems they need to solve, whether that’s implementing an efficient caching strategy for a distributed db query or executing a solid flying armbar that doesn’t snap a collarbone on landing. People pay attention in different ways, focus on different parts of problems, address issues in different orders, and in general are different in countless ways.

Pairing with different people, therefore, can help (and has helped me) to think about problems from angles different from how I might usually approach them. I can then add that perspective to my toolbag of development tricks to be used at any time. But I would never have learned to do that without being exposed to how it worked for someone else. I might read about the same technique in a blog, but trying it without seeing that it works for some people reduces the possibility that I will persevere with it if it doesn’t show immediate benefits for me.

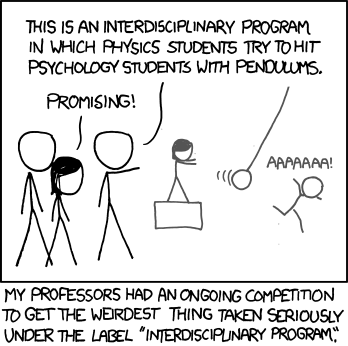

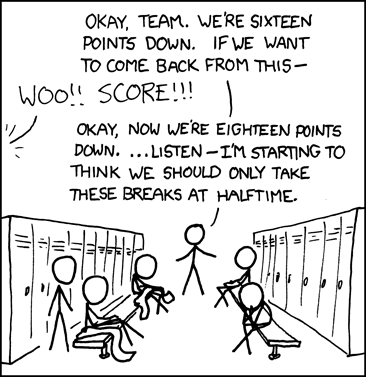

If you compete instead of collaborating, the end result can suffer

© xkcd.com

© xkcd.com

Every man lives by exchanging. Adam Smith

This is a difference in mentality when training versus the mentality required for performance in competition. In competition, all your focus, all your effort, is designed to create openings, exploit weaknesses, and weaken the position of your opponent, and leave them open to attack.

Crucially, however, that mentality is left behind in the ring/cage/octagon. In training, which is where I would draw the parallel with pairing, you can have the same attitude with a different focus. You may still be identifying holes in your training partner’s game, openings you might choose to exploit or not, and taking advantages of weaknesses, but you do so in order to help them improve and shore up those weaknesses, limit or eliminate those openings, and become a better fighter. And they are doing the same to you.

If you are both pushing each other, the end result is that both of you become a better fighter, and your training bouts (which we can think of as the product in analogy to the product of pairing) will be of a higher quality, drawing more attention. If, in training, your focus is solely on winning and not on self-improvement, you will quickly plateau. In order to improve, you have to learn to subordinate your ego to the benefit of the larger goal, improving as a martial artist.

Accepting criticism, accepting loss, is part of that, and that’s the lesson I’ve found most applicable to pairing. Joining any kind of collective is for many good reasons abhorrent to humans – that’s why the Borg are probably the most popular adversaries on Star Trek. Individuality is prized, collectivism and subordinating one’s self to a higher cause is feared (or admired when done, because it is so rare). Learn this skill, and you will be that rarest of developers: one that people want to pair with.

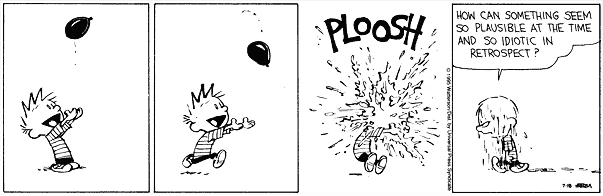

Dwelling on mistakes is counter-productive

© Bill Watterson

© Bill Watterson

Have no fear of perfection - you’ll never reach it. Salvador Dalí

Now here I think I need to clarify what I mean. The difference between dwelling on mistakes and focusing on improvement through removing them can be summed up as the difference between two attitudes. One says, “Next time, I will….” The other says, “If only I had….”

We learn when looking at accounts of samurai training, and from the Budō manual the Hagakure, that the samurai mentality that was encouraged was one of equanimitable acceptance of death. Mistakes in training, which in a real encounter would have led directly to death, thus become learning experiences because they cannot be anything else. “You are dead. You cannot change what you did.” Mistakes thus become irrelevant to one’s training except to the extent that they can be avoided due to prior experience.

This is something that carries over not only to pair programming, but also to one’s own individual coding – but it is in pairing where its real benefit is experienced, because it is in pairing that the temptations to focus on one’s mistakes; to make excuses for ones past code; to reinterpret one’s thinking processes through rose-tinted glasses; and generally to present oneself in a more flattering light, are magnified. But if we remember that mistakes cannot be changed, they can only be learned from, we can let go of the need to do any of those things, accept that they are in the past, and move on with what we can accomplish today.

Repetition is the only path to instinctive ability

© Bill Watterson

© Bill Watterson

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit. Aristotle

We’ve all heard the maxim, “Practice makes perfect,” and some of us may even have read Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers”, in which the now-famous claim of 10,000 hours of practice before attaining world-class performance is made. Gladwell has since retreated from that claim, and there are many modifications to the maxim in existence. Two of them have featured centrally in my martial arts training, and they are not only applicable to martial arts training and pair programming, but to any kind of endeavour where repetition builds skill and judgement.

First: “Practice makes permanent.” The meaning is hopefully clear, and is elucidated by the second variation: “Perfect practice makes perfect.” It should be obvious that practise of the wrong things, without correction (either self-correction or criticism and adaptation) will not lead to perfection. We need feedback in order to adapt our practice, and the best feedback is that which is immediately connected to the activity in question. Pairing is thus the best way for a developer to incorporate improvements to their own practice of development.

One method for doing this that I have found useful is the “Three I’s” method: Introduction; Isolation; Integration. First the new concept or method is introduced; then it is practised in isolation, and increasingly complex examples are used; then finally it is integrated into the pre-existing set of techniques available. This model of skill acquisition can be seen to follow the 4-stage model of competence.

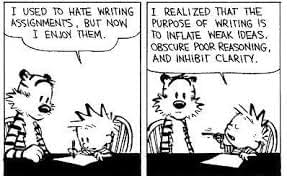

If you can’t explain something in a few different ways, you don’t really understand it

© Bill Watterson

© Bill Watterson

The art of teaching is the art of assisting discovery. Mark Van Doren

If you read the competence article linked above, you’ll note that at the end it talks about a potential 5th stage of competence. Now, there are a few competing possibilities for the 5th stage, and they fall broadly into two categories: either an increase, or a decrease in competence following the achievement of the 4th stage.

As I’m an optimistic kinda guy [This from the guy who insists the glass is twice as large as it needs to be? – Ed.], I prefer to focus on the positive 5th stage, which is where competence has reached a level where the skill can be taught, and the stages of acquisition shortened for new learners due to the degree of understanding possessed by the teacher.

It is clear from many disciplines that one way to gain increased understanding is to attempt to articulate one’s understanding in response to prompts, questions, and situations where one is collaborating with a junior (or even an equal, or a senior) colleague. [Ref: point 1]. For many, it is this very articulation, the requirement to put one’s understanding into words so that they can be comprehended by others, that deepens one’s own understanding.

The more one tries to do this, the better one gets at it [ref: repetition]. And the more different people one teaches, the more different ways of learning and modes of skill acquisition one encounters. One gains thereby a facility for understanding the mental models underlying the direction a colleague’s questions might be coming from, and can address oneself to the mental model in addition to answering the question. I have seen this bear astonishingly rapid fruit when an experienced instructor can correct someone’s mental model of a technique with merely a single word or phrase, entirely transforming how the recipient thinks about what they are trying to accomplish.

If our aim as pair programmers is to improve both how we code and how we pair effectively, I would argue that we should be looking to effect the same kind of change.

Recognising that different people learn in different ways will become instinctive with repetition and exposure to that truth, and we can tailor how we engage with people in order to pair with them most effectively. The more you pair, and the more different people with whom you pair, the more broad your toolkit for effective pairing will become as you explore different options for engaging with the problem space.

Talking is no substitute for doing

© xkcd.com

© xkcd.com

Think like a man of action, act like a man of thought. Henri Bergson

Or woman, of course. But the substance of the quote is fundamental to the way in which effective developers approach problem solving, in my experience. Think, and talk through approaches, always with a view to how those thoughts will ultimately be implemented. And when it comes to action, the carrying out of our chosen course needs to refer back to what we agreed. Should a new approach become apparent, we do not plunge forward, but consider the implications of progressing down the newly revealed path. This consideration may only take a few minutes, but it needs to happen.

Following from the point about repetition, above, if all we do is talk, all we’ll get good at is talking. We need to do in order to get better at doing. And thus, in order to get better at pairing, we need to pair. We need to pair effectively, and inspect and adapt how we pair so that next time it’s an even better experience.

Calm is not the same as slow

© Tatsuya Ishida

© Tatsuya Ishida

The cyclone derives its powers from a calm center. So does a person. Norman Vincent Peale

You may have heard of the state known as “flow” or being “in the zone” [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(psychology)] as being a desirable one to achieve, but which can be easily broken by distractions in one’s immediate environment: interruptions from colleagues; loud music or tannoy announcements; alerts popping up on your screen; family calling at inopportune moments; lunchtimes; and many others. Techniques for not breaking the flow state once it has been achieved are many, but most of them require the elimination of potential distractions. I’d like to introduce a few concepts from Zen Buddhism, also widely known by practitioners of Japanese martial arts, which may help.

- Mushin no shin (無心の心) translated usually as “no mind” or “the mind without mind” is a state of relaxed awareness and openness. One anticipates nothing, is preoccupied by no thought or emotion, so one is ready to respond to anything.

- Zanshin (残心) translated as “remaining mind” is a state of complete awareness without focus on any specific part of that awareness. One is alert and ready to respond to any change in the environment.

- Fudōshin (不動心) translated as “immovable mind” or “unmoving mind/heart” is a state of imperturbability, in which the advanced practitioner remains while responding to change in the environment, and which persists afterwards.

Taken together, these states can help one not to break flow even if it is interrupted. Advanced practitioners of the Japanese martial arts try to carry the awareness states into their normal lives outside the dojo, and it is entirely possible to allow oneself to slip into and out of the state of mind that is most useful for achieving one’s goal without being mindful of the goal itself. The immovable mind permits retention of focus on a task while responding to a stimulus outside the task. Shifting focus thus is not necessarily a detriment, so long as the appropriate mindful state can be maintained.

All of the above states are useful for sole development activity, but there is a fourth state which is particularly useful for pairing. It is shoshin (初心), or “beginner’s mind,” and refers to an attitude of eager openness to new experiences and a lack of preconceptions, even when working at an advanced level. In my opinion, there are very few developers who are not eager to learn new things, new ways of working, new technologies: but there are few indeed who come to new concepts as a beginner would, emptying their mind of what has gone before and soaking up concepts and information as a beginner. Only afterwards do they process and filter the information and relate them to their previous framework of knowledge.

TL;DR

It’s an unfortunate truth that many developers separate the act of development from how they live the rest of their lives. We generally know when we are most effective, but often ignore other aspects of what makes any particular dev session productive or otherwise. Plus, confirmation bias and attribution error can quickly lead us to adopting strategies for productivity which are actually harmful. Once in a while, it can be useful to step back and look at our process, inspect it and see if there are any improvements that we can find to make. And looking beyond the circle of our colleagues and peers for inputs into that can help enormously. I hope the above has given some food for thought.

…and if it brings more eager students to the martial arts, even just one curious quick-brained dev, I’ll consider that a success.