Xamarin provides a common development experience for creating cross platform mobile applications. The aim of this post is to highlight the design techniques available and options Xamarin provides for maximising code reuse, thus ensuring cleaner code and increased productivity. The anatomy of native Xamarin Android and iOS applications will be initially discussed and used as a starting point for exploring these concepts.

What is Xamarin?

Xamarin is a Microsoft owned software company that provides cross platform implementations of the .NET Framework that target Android, iOS and Windows devices. With increased support in Visual Studio it provides a common development experience for .NET developers to create cross platform applications. The most common usage is to develop applications targeting Android and iOS mobile devices, thus these applications will be this blog post’s primary focus.

Native Xamarin Applications

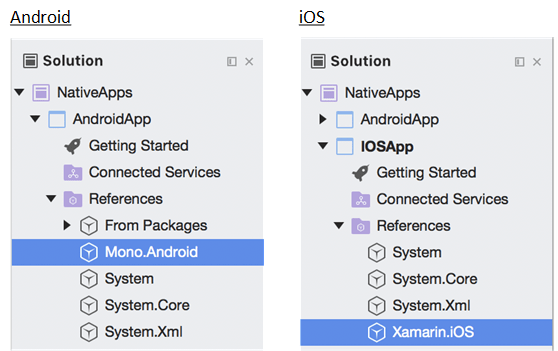

Xamarin facilitates the development of Android and iOS applications by providing the Xamarin.iOS and Mono.Android libraries, as shown in Figure 1. These libraries are built on top of the Mono .NET framework and bridge the gap between the application and the platform specific APIs.

The following is an explanation of how native Android and iOS Xamarin applications are structured including the different components and their relationships.

Native Android Applications

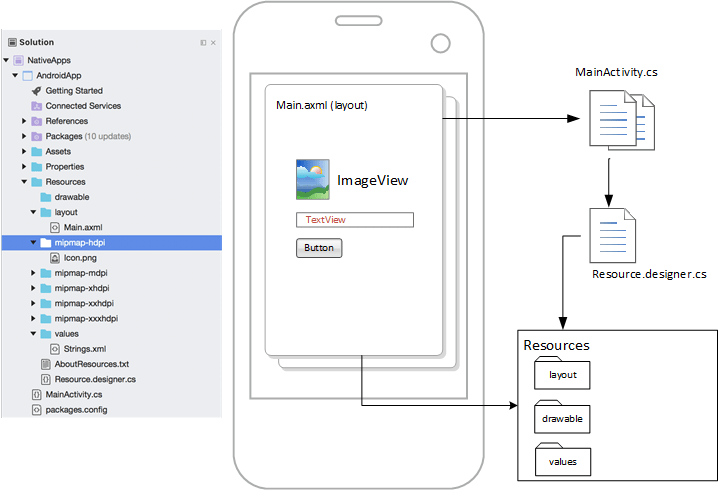

Figure 2 outlines the project structure and the architecture of a Xamarin Android application. An Android application is a group of activities, navigable using intents, that provide the code that runs the application. The entry point of the application is the activity whose MainLauncher property is set to true, which is the MainActivity.cs by default. Activities that provide a view have an associated layout template that is made up of view controls. Activities and view controls reference the following resources:

- layouts – view templates loaded by activities.

- drawables - icons, images etc.

- values – centralised location for string values.

- menus – templates for menu structures.

The Resource.designer.cs class provides an index of identifiers for all the resources in the application. This class is referenced by activities and view controls to create an instance for use in the given context.

Native iOS Applications

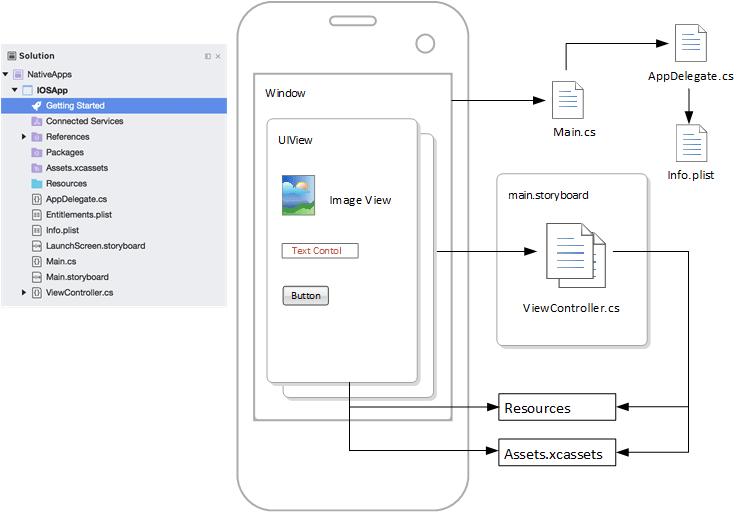

Figure 3 shows the project structure and the architecture of a Xamarin iOS application. The application is made up of several view controller classes and associated views, collectively known as scenes, that are loaded into the main application window. View controllers are grouped into storyboards with each storyboard having an initial view controller. Views are made up of a view controls used for display or user interaction. Navigation between the view controllers is handled via segues.

The entry point for the application is the main.cs class that instantiates the specified AppDelegate.cs class, which loads the initial view controller of the default storyboard set in the Info.plist configuration file. Resources such as images, videos etc are referenced from the Resources and Assets.xeassets folders by view controllers and view controls. The AppDelegate.cs class includes delegates that handle application events and the view controllers handle the lifecycle for a given view.

Native Android vs Native iOS Applications

Although the above two applications target different platforms, their architectures have many similarities. They are both event-driven with actions performed by delegates wired up to both application and UI events. The display in both cases is driven by views interacting with code behind classes, which for Android is layouts and activities, and for iOS is views and view controllers. These similarities continue as view controls are added to views to provide content display and user interaction.

Xamarin takes advantage of these similarities to provide a common UI development experience. While this blog will explore this a lot more, it suffices to now concentrate on how code can be shared between both Android and iOS applications.

Common Code

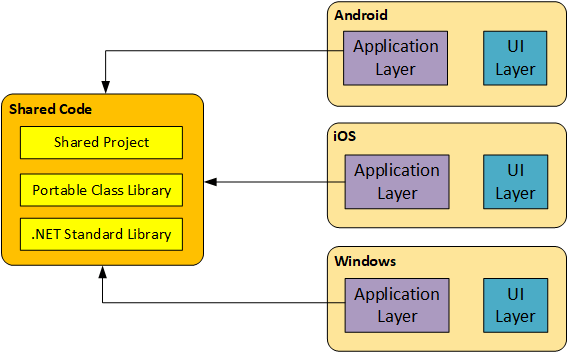

There are a couple of methods that allow code to be reused across projects in Xamarin: Shared Projects and Class Libraries. Figure 4 shows the available options to refactor common code out of the application layer of the platform specific projects. It also illustrates that the extracted code can be consumed by any .NET applications, thus further increasing the scope of its use.

A Shared Project differs from class libraries as the code is copied and included in each application assembly during compilation, thus no separate assembly is created. This non-separation of outputs does have its disadvantages, for example sharing the code beyond the scope of the solution becomes problematic, and unit testing components in isolation from the application is not possible.

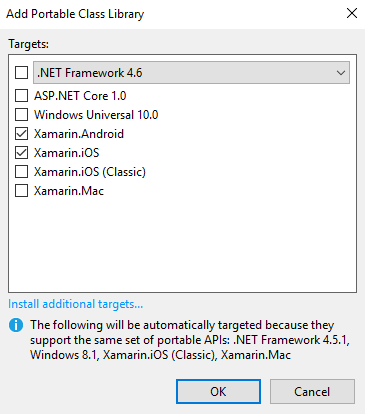

A PCL (Portable Class Library) is a type of class library introduced to address the issues highlighted with Shared Projects. Figure 5 shows an example the available platforms that can be selected, and illustrates that the use of PCL’s is not restricted to just Xamarin mobile applications. The compiled assembly can be referenced by other projects, however there are still drawbacks as the target platforms supported need to be selected on creation. Consequently, only a cross section of the APIs across the selected base libraries are available for use, limiting the available scope.

The latest, and recommended, method to share code is using .NET Standard libraries which provide a wide ranging and consistent API with full compatibility across the latest versions of the .NET framework, .NET Core and Xamarin, thus alleviating the limitations of the PCL approach.

In Xamarin the concept of code sharing can be taken even further by implementing the MVVM pattern. This will be discussed next.

MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel)

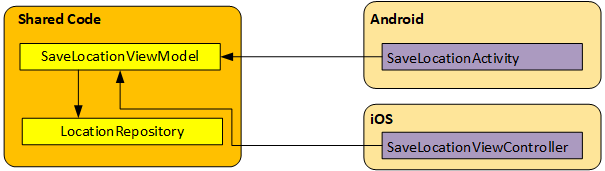

Xamarin, as previously discussed, is based on an event-based architecture in which methods handling UI and business logic would traditionally reside in code behind files. Figure 6 highlights how the MVVM pattern moves the responsibility of handling view data and events into view model classes and away from activities and view controllers. The view model classes then reside in shared code, which is referenced by the application projects, leaving the activities and view controllers with the platform specific responsibilities. The connection between the view and view model components is handled via data binding which ensures properties and methods on the view model are wired up to the view controls. Apart from code reusability. another advantage of data binding is that the view reflects the view model’s state through two-way binding. Consider the example of a price calculator, updating the gross amount view will feed through to the view model, causing the net value to be recalculated, which will automatically reflect on the view.

Figure 6 does highlight one problem with the MVVM approach that needs to be addressed. The example shows the application saving a devices location which will require retrieval of its GPS coordinates. The code to handle saving now resides in the shared code but the platform specific libraries that handle retrieving the devices location are referenced by the application projects. How can the view model pattern be implemented to handle platform specific functionality?

Shared projects provide a mechanism for including platform specific code by using conditional compilation. Android and iOS projects have default compilation symbols configured which can be used to include platform specific code. Shared projects are different to class libraries as they act more like extensions to the projects that reference them, thus they have access to the libraries referenced by those projects. The compilation symbols can be used to implement platform specific code in the same area, which is then pulled into the specific project during compilation.

#if __ANDROID__

// Android-specific code

#endif

#if __IOS__

// iOS-specific code

#endif

This is not ideal as the code does not follow good code design principles, for example there is no separation of concerns, thus adding complexity.

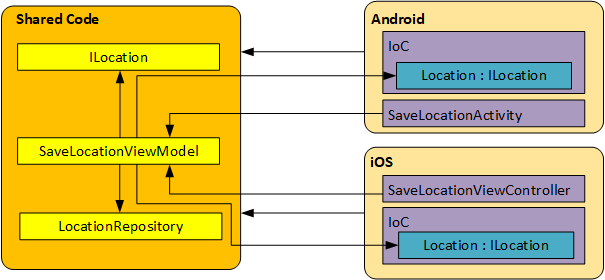

Figure 7 highlights a more elegant, and preferred, approach that follows SOLID principles, in particular the Dependency Inversion Principle. The Shared Code includes an ILocation interface that is referenced by the view model, and by the application projects. The application projects implement their own specific version of the ILocation interface in the form of a Location class. An Inversion of Control (IoC) container, which is configured in the application projects, is used to implement the Dependency Inversion Principle by injecting its own version of the Location class into the view model, thus at runtime the platform specific Location class will be used to retrieve the devices location.

There are several MVVM frameworks that are available for Xamarin development. MVVMCross and MVVMLite are commonly used examples, which also provide IoC container support, but there are others available that may better suit your needs.

The previous sections have concentrated on code reuse, next let’s consider the UI.

Xamarin.Forms

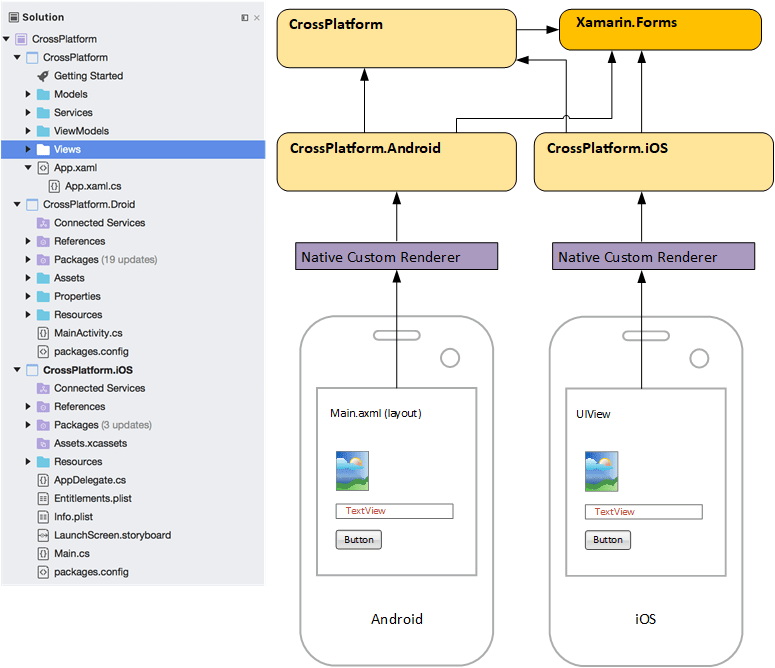

Previous sections have outlined how code sharing can be achieved between platform specific applications but Xamarin also provides an approach for sharing the UI components. Xamarin.Forms takes advantage of the commonality between the architectures of native Android and iOS applications. Figure 8 shows the project structure of a Xamarin.Forms project in Visual Studio and the relation between the components involved.

An Android and iOS project is created, as before, along with an additional third project which contains the common UI components. A Xamarin.Forms project uses XAML mark-up for creating views and accompanying code behind pages for handling behaviour. Xamarin.Forms also provides view controls that can be referenced both in the XAML and the code behind for creating the user experience. The application class, app.xaml.cs, is the entry point that loads the initial page for the application and contains delegates for handling application level events.

The entry points of the Android and iOS projects, MainActivity.cs and AppDelegate.cs, are configured to load the common Xamarin.Forms App class. Once the app is initialised, platform specific renderers translate the pages into activities or view controllers, and the views and view controls into their Android, or iOS, counterparts at runtime, thus providing the native application experience.

As Xamarin.Forms is based on the .NET framework and XAML it can also be used to create the UI experience of applications targeting Windows devices. Apart from reusability, another advantage of using Xamarin.Forms over native Xamarin application development is that MVVM support is built in out of the box through simple refactoring of the XAML mark-up and associated view models.

However, although Xamarin.Forms will handle most requirements there may be limitations when developing against specific platforms. Xamarin.Forms does provide extension through custom renderers but this may potentially create greater complexity in your application which can often be better implemented using the native approach.

Summary

Hopefully this post has provided a high-level understanding of how to approach the development of cross platform Xamarin applications. I mentioned earlier how .NET Standard libraries are now the recommended approach for implementing common code and how implementing the MVVM pattern, in conjunction with good design practices, can increase code reuse even further. Finally, l discussed how reuse can be extended to the UI layer by using Xamarin.Forms to build common UI components and highlighting that this should be sufficient in most cases unless requirements steer towards a more richer native UI experience.

The techniques and options covered show how the responsibility of the native application projects can be limited to managing only platform specific functionality and resources leading to better separation of concerns, and consequently higher code reuse and productivity.