It’s always important to remember that whilst Behat can be just used as a scripting language, in order to get the many benefits associated with BDD then you should always view your scenarios as ‘Executable Specifications’ for features that deliver business value and that are written in the domain language of the business. Your scenarios can then be tested using Behat by building small re-useable components, based on the good principles of Encapsulation, Separation of Concerns, and Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY). This post then is about the beginning the journey from Behat Novice to Behat Pro by understanding how to use the Page Object Pattern to build that encapsulated, reusable, code that marks out the expert from the novice. The complete code for this can be found at https://github.com/andrewlcg/behat_tutorial and although we’re using Behat here the same principles apply equally to any BDD framework.

Our scenarios should provide the complete documented specification for the software being delivered, and can be executed to provide validation of the system in a timely manner. To illustrate how to create effective Behat features, we’ll use the following example requirement written as a typical user story.

As the Corporate Lawyer

I want to ensure that in addition to entering their details the user agrees to the Terms of Service when signing up

To ensure that we can justifiably suspend the account if they break the Terms

NB two things here

- This is a requirement for the ‘Corporate Lawyer’. It’s too easy to write ‘As a User’ for each scenario, but this requirement is definitely not one being driven by the needs of the user.

- There is no reference to any specific fields, only that the user has agreed to the Terms of Service. The mechanism for agreeing is an implementation detail, but isn’t part of the requirement.

Starting with scripting

Someone new to Behat will typically write the specification like this:

When I go to "https://accounts.google.com/SignUp"

And I enter "Larry" in "First"

And I enter "Page" in "Last"

And I enter "larry.page@mailinator.com" in "Username"

etc…

And I press "Next step"

Then I should see "In order to use our services, you must agree to Google's Terms of Service."

This specification has a number of inherent problems though:

- It’s brittle - If any of the fieldnames, or their arrangement (eg we have a single ‘name’ field) changes, then we need to rewrite the specification. e.g. if we added or removed a field we’d need to modify the feature file even though the specification hasn’t changed.

- It’s not reusable - if we wanted to reproduce this functionality as part of another page we’d have to copy-and-paste the steps. It’s not DRY!

- It’s not even really a specification. The completion of those specific fields is not mentioned in the requirement, neither is the exact wording specified.

Progressing to Page Objects

Let’s start by rewriting the specification so that it fits the requirement:

Given "<user>" is on the signup page

And they complete the signup form but do not agree to the terms of service

Then they should see a warning message telling them to accept the terms of service

And should be on the signup page

Examples:

|user|

|Larry|

|Sergei|

This specification is much better. It describes in plain language, with the minimum of jargon, what needs to be implemented to meet the requirement. It’s not brittle - it doesn’t rely on any specific implementation, so that if field names change then the specification, quite rightly, isn’t affected.

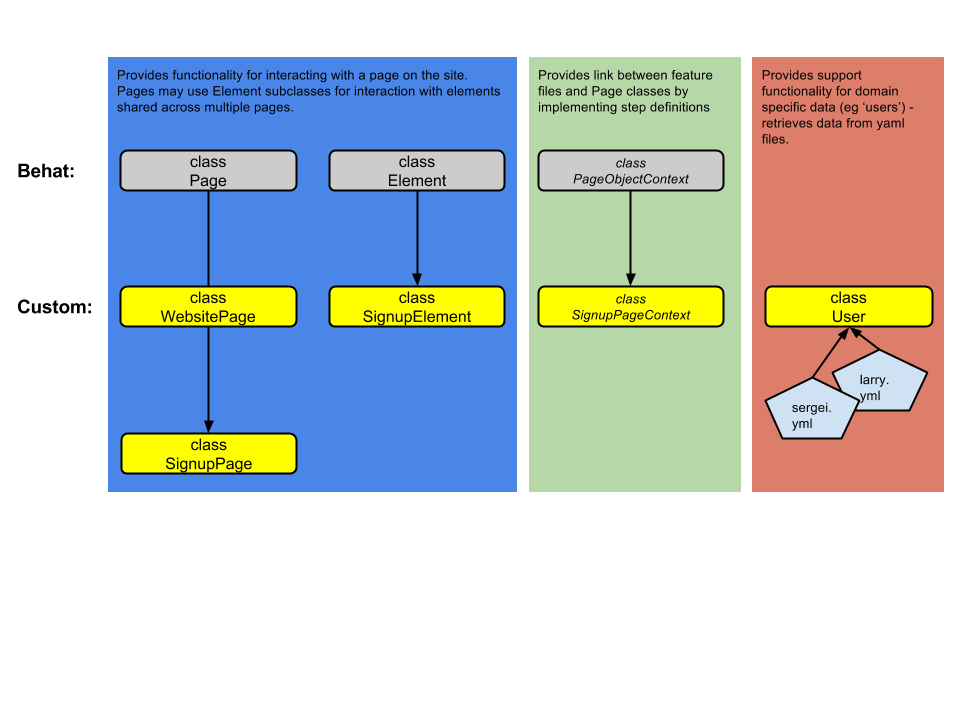

But, where do we implement these new step definitions such as “And they complete the signup form but do not agree to the terms of service”? The answer is that we encapsulate the steps by implementing the Page Object pattern. This pattern enables you to interact with the functionality provided on a page, but hides the implementation behind an API (in reality, just a set of methods). The specification, encoded in a feature file, calls steps that are implemented in a PageObjectContext which in turn uses Page and Element objects to manipulate the page’s DOM. A very high level view of this can be seen below. (Click to see larger version)

You can read more about how Behat implements the Page Object pattern at http://extensions.behat.org/page-object. As far as our example goes let’s take a look at the first couple of steps. We have three distinct components - a user, a page and a form within that page. Let’s look at the first step in the specification:

"Given "<user>" is on the signup page"

This step is implemented in the SignupPageContext as follows:

public function isOnTheSignupPage($name) {

if (!$this->user = User::load($name)) {

throw new Exception("Failed to load user for {$name}");

}

$this->getPage("Signup Page")->open();

}

User::load simply returns a User object which contains information about a user, such as their name, email address etc - this information is stored in a YAML file, so it’s not tied to any implementation and can be re-used across the project. This gives us a ‘user’ with attributes that we can use across all of our specifications.

$this->getPage("Signup Page")->open() is defined within Behat’s PageObjectContext class and auto-loads a class we’ve defined called SignupPage and it simply opens the url stored in that object’s $path property.

The next step “they complete the signup form but do not agree to the terms of service” is again implemented within the SignupPageContext and, after checking that we have a valid user, does the following three things:

$this->getPage("Signup Page")->enterUserDetailsOnSignupForm($this->user);

$this->getPage("Signup Page")->doNotAgreeWithTermsAndConditionsOnSignupForm();

$this->getPage("Signup Page")->submitSignupForm();

These should seem quite explanatory in their intent. Let’s examine what the first one does:

$this->getPage("Signup Page")->enterUserDetailsOnSignupForm($this->user);

This is implemented within the SignupPage class as follows:

return $this->getElement('Signup Form')->enterUserDetails($user);

this auto-loads an object of class SignupFormElement and calls its method enterUserDetails. This encapsulation enables us to re-use the functionality of the signup form on other pages, and prevents pollution of methods between classes.

The enterUserDetails method contains a simple implementation doing exactly what is required to enter the user details in the signup form. Again, this should be self-explanatory:

$this->fillField("First", $user->first_name);

$this->fillField("Last", $user->last_name);

$this->fillField("Choose your username", $user->email);

$this->fillField("Create a password", $user->password);

$this->fillField("Confirm your password", $user->password);

$this->fillField("Your current email address", $user->email);

Finally by taking a look at the layout of the files, we can see that the functionality is clearly separated and encapsulated - each class in the hierarchy is responsible for interacting with a well-defined part of the signup process.

├── bootstrap

│ ├── Page

│ │ ├── Element

│ │ │ └── SignupForm.php

│ │ ├── SignupPage.php

│ │ └── WebsitePage.php

│ ├── Resources

│ │ └── Users

│ │ ├── larry.yaml

│ │ └── sergei.yaml

│ ├── Subcontexts

│ │ └── SignupPageContext.php

│ ├── User.php

│ └── WebsiteFeatureContext.php

└── website

└── ensuretermsconditions.feature

You can read more about features as executable specifications in the excellent “Specification by Example”. More information about Page Objects from Selenium’s perspective can be found at http://code.google.com/p/selenium/wiki/PageObjects.